Baffling market optimism

Posted 9 October 2020

Following the unsteadiness of September, markets have further regained their composure and continue to drift upwards. This stands in stark contrast to the flow of bad news. The White House, centre of power for the mighty US, has become a COVID hotspot, similar to many regions across Europe and the UK. Meanwhile, the Brexit negotiation noises have been loud enough to make those worried about the economic impact of the pandemic even more ill.

And if the nation was split over Brexit, then the debate over the right way to deal with the second wave of the pandemic is drawing yet more dividing lines. Our own Chancellor is said to be very much against a further drag on the economy, while many other MPs are against renewed restrictions on freedoms. Enforcement of social distancing is proving much less effective, especially when trying to do it locally. Rishi Sunak is right to be worried by the stalling of the growth rebound across the UK’s service-sector dominated economy, even though similar scenes are playing out across Europe and, perhaps to a slightly lesser degree, in the US.

But markets everywhere are behaving as if none of this really matters. Almost every capital market-based indicator (that we look at) tells us investors are increasingly confident about an upward path for economic growth over the medium term.

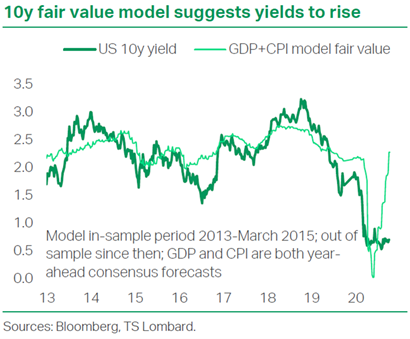

Long-maturity bond yields have risen across the board, five basis points (bps) in Germany and France, 15 bps points in the UK and a substantial 20 bps in the US – usually a sure sign that things are looking up, not down.

These signals go beyond the auspicious government bond markets. Credit spreads – the premium companies pay on their loan capital versus the government – have declined somewhat. Stocks that thrive when the economy rebounds (cyclicals) have also performed well, beating the more defensive large-cap growth stocks of the ‘Big Tech’ world, previously the favourite ‘fear-trade’ investment during the stock market recovery. Globally, small- and mid-sized stocks have outperformed large caps, a trend which has been going on for over a month.

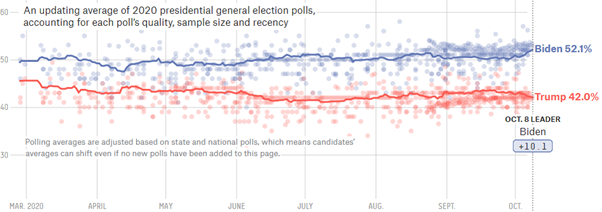

As we first discussed last week, behind it all is a rather unexpected driver. Global investors seem – somewhat unexpectedly ‑ to be warming up to the prospect of the Democratic Party sweeping the board in November’s elections. This week has seen the US opinion polls signalling a widening advantage for Joe Biden in the Presidential race, plus a potential Democrat takeover of the Senate (as well as retaining the House of Representatives).

If this were to come about, the Democrats would have at least two years to enact their Keynesian program of pump-priming the US economy back to its former health through government spending and investment. The perception seems to be that the other elements of their programme – higher taxation on larger companies and a further 2% income tax on the wealthiest individuals (as well as an end to the regulatory ‘wild-west’ of the tech giants, which we explore in greater depth in the article below) would cause a rebalancing of corporate profits but, on balance, would enhance the sum total of economic growth. As an added bonus for the world, this may lower the value of the US$. A Trump defeat should also ensure greater visibility of White House trade policies – and much less disruption – which together with a lower US$ have the potential to kick-start a much-needed global trade cycle.

Interestingly, equity markets have coped well with what has been the sharpest rise in yields for some weeks, given that the rise brings with it some less than positive aspects for equities. Namely, higher yields would challenge the notion that equities are ‘the only show in town’ which has been helped support historically high equity valuations, while also challenging the longer-term viability of many debt-laden companies. So, any rise beyond the normal day-to-day volatility might cause a derating.

This leads us to looking at the other fundamental of equity valuations: earnings. As research from US investment bank JP Morgan has pointed out, while it is still very early in the run of results for the Q3 company reporting season, so far there have been no horrible surprises. Equity analysts have responded to the reasonable start by raising sales and earnings expectations. In other words, the starting point for profits is stable and next year’s earnings growth visibility is improving. This may be more than enough to offset the downward pressure on valuations from a rise in long yields.

Of course, this particularly benefits more cyclical companies, where the valuation advantage comes from the nearer-term (i.e. three to five years) rather than the more long-term time horizon of growth companies. For the short- to medium-term, the discount rates (yields) have hardly moved and can be expected to be held low by central banks in almost any scenario, in order to ensure that interest rate policy does not derail the economic stimulus efforts of the governments’ fiscal programs.

An important component here is that most economists and investors (us included) do not seem to fear that huge government spending will result in big rises in the cost of the debt, because it seems reasonable to assume that economic growth in the near to medium term – and taxes receipts in its wake – will exceed the interest that governments are required to pay. Our research partner TS Lombard shows this is in its model of ten-year US Treasury yields relative to economic growth and inflation. It assumes that the Fed behaves as it did up to 2015:

The ‘bond vigilantes’ may be a rare species these days, but they can still be spotted and they would now point out that even under this scenario, the longer-term perspective would still be bleak. This is simply because under this orthodox scenario, where central banks keep only the short- to medium-term yields low through their forward guidance in rates, the further out maturity yields would still be pushed higher. This could result in the worst of both worlds: a much-enlarged government burden and arduous company debt levels, which would likely ramp-up fears over corporate defaults and destablise capital markets.

Therefore, the fact that markets are currently not panicking over the beginning rise in longer-term yields tells us that markets are also taking the US Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Jerome Powell at his word; that the Fed will respond benevolently to more issuance of both government and corporate debt when it wants to borrow to invest. But the only way to achieve that is for the Fed to look beyond its traditional interest setting policy tools. This requires long-term commitment to capping longer-term yields by means of – yes, you guessed it – quantitative easing. Or, in practical terms, by purchasing longer-term debt, rather than leaving it to the forces of supply and demand in the freedom of capital markets to determine what the yield should be.

Some will criticise this as an irresponsible undermining of capital market freedom, and an erosion of the public trust in value of money through sustained financial repression, long beyond the pressures of the COVID‑19 crisis. Others will describe it as the only way to return the global economy to a sustained growth path, by dealing with the universally-raised debt levels around the world in the same way that western societies did with their war debts after World War II.

This process is called a “terming-out”, through the issuance of multi-decade maturity debt. In our view, this would be a hugely positive signal, and is one which we think will have to come. The ultimate causes for the risen debts may be different to war periods, but the potential aftermath/after-effects appear very similar. On this basis, we would expect that our free market economies with their relative financial stability are just as unlikely to come to an end, if we deal with the challenge in a similar manner now, as they did in the 25 years that followed WWII.