Delicate equilibrium

Posted 26 August 2022

All eyes are on the world’s central bankers this week, who are guests of the US Federal Reserve (Fed) at its annual conference in Jackson Hole, Wyoming. Markets are particularly eager to hear what Fed chair Jay Powell has to say – hoping that his speech will give hints on the direction of US and global monetary policy. We write this before Powell has had a chance to talk (3pm London time) but there has been ample speculation already. Market expectations are of a mildly hawkish tone, with a repeated focus on controlling inflation and cooling wage demands.

This has made investors nervous. Equities rallied last month on the back of improved valuation metrics, which were themselves propelled by falling bond yields, making stocks more attractive by comparison. But bond market positivity was in large part down to shifting expectations of central banks towards a less hawkish stance. A weakening global economy and cooling prices, the thought goes, will necessitate a softer approach from the Fed.

Jangling nerves meant a pullback in markets last week. This was widely anticipated, and perhaps the fall was shallower than one might have expected, given the weakening global economic outlook. Growth expectations have declined significantly due to the energy price shock (Europe/UK) and the increased cost of finance from higher interest rates (US). This is now reflected in business sentiment, as well as very clearly in consumer confidence levels.

The UK has been particularly hard hit by the latest news of a near doubling of Ofgem’s energy price cap for the winter months. The arrival of a new prime minister must surely bring more government support for households. The difficulty – as trailing leadership candidate Rishi Sunak points out – is in giving aid to the worst-off without boosting overall demand too much. The latter would worsen the supply side problems and keep inflation soaring. This is likely in France, with its blanket household subsidy, and it could well be the same in the UK if the new government opted for a fixed energy price cap instead of direct support payments (‘handouts’).

Even with government help, households will inevitably struggle. In this situation, the key policy objective is to ensure people are not hit with the double whammy of job insecurity on top of the energy price shock. That is a significant threat, given the current difficulties facing businesses. There is no price cap for businesses, meaning energy costs have increased several times over. Providing support for those businesses – particularly small and medium sized enterprises – is imperative in the months ahead. This is akin to the situation at the start of the pandemic: without help, small businesses will have to shed staff or face total collapse.

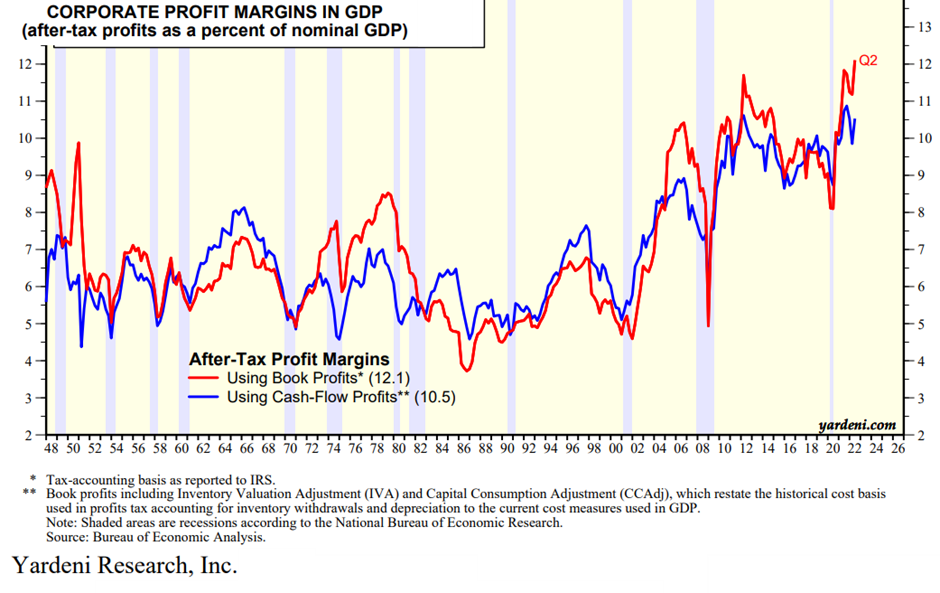

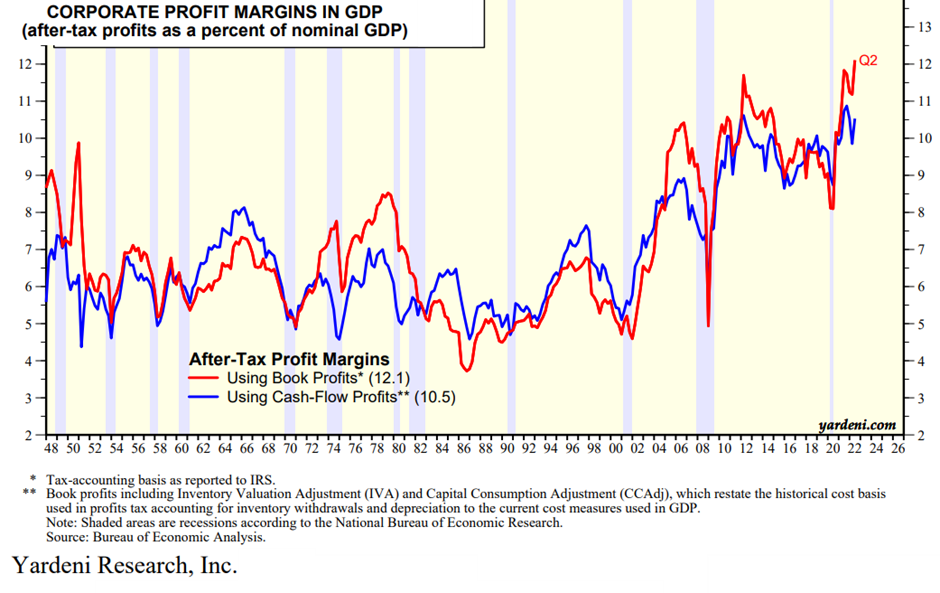

In the US, cost pressures are less intense, as the energy market is less dependent on Russia, and therefore less sensitive to Putin’s war on Ukraine. Even so, US consumer and now also business confidence has taken a downturn, signalling a slowdown in growth. But despite the gloom, profit margins have held up nicely across the Atlantic. In fact, recent data shows US corporate profit margins expanding to their best ever ‘book profit’ level in the second quarter of 2022. Cash flow is still remarkably strong, giving companies a big buffer for the difficult times ahead.

However, the strength of corporate America will undoubtedly be politically unpopular, particularly if after inflation household incomes continue to suffer, as a result of central bank action. Powell and his team will be well aware of this, and might therefore think corporate profits can take a harder hit from tightening monetary policy. While this is unlikely to make credit spreads (the difference between government and corporate bond yields) too wide, it would make things more difficult for US businesses, and reverse the goodwill we have seen in markets.

So, are investors sleepwalking into a downturn? Some certainly are taking that view – backed up by those considerable headwinds for the global economy and an apparent underappreciation of risks. We see things slightly differently. We suspect that this year’s downward stock market volatility has led to a fragile equilibrium between the negative impact on earnings and the positive reaction that could come from central banks. Should the Fed prove successful in engineering an inflation busting slowdown in the labour market without an economic crash landing, there will be less upward pressure on bonds.

‘Delicate’ is the key word here. The fine balance of risks and rewards does not mean we expect markets to trade sideways. Rather, we expect a continuation of the volatility we have seen this year. Particularly interesting is what this means for different investment styles. So called ‘growth’ stocks, like big tech companies, are usually heavily dependent on bond yields, as they are long-duration assets and therefore sensitive to assessments of long-term risk premia. But bond yields are clearly no longer the only driving factor behind these stocks.

The biggest growth companies – Amazon, Netflix, Microsoft and Apple, to name a few – have unquestionably come of age and are now by far the biggest players in their respective sectors. This means that their growth is not so much at the expense of old businesses, but rather a reflection of the market as a whole. These days, they are much more exposed to the ups and downs of the economic cycle. This creates new dynamics and new avenues for growth and investment returns. For the discerning investor, this delicate equilibrium could be full of opportunities.