Fed up before Christmas

Posted 9 December 2022

One of the first principles of any sound investment process is to permit and nurture the discourse of differing opinions in order to generate the most robust insights and decisions possible. Unsurprisingly then, here at Tatton, this is exactly what has characterised this year, as we have absorbed various guidance and deductions regarding possible underlying reasons for asset price movements. As the year comes to a close, some of the year’s big trends have showed signs of stopping or even reversing, and we have debated the ‘reasons’ for those changes vigorously. This process is important because we must understand the past and the current state to have any chance of understanding where markets might go.

Discussions tend to focus on one or two factors, but markets are always the balance of many drivers. Each debater will have their own valuable input about how the identified factors will change, and which new ones will emerge.

Often the most important question is “are we missing something”?

One aspect of this is that financial reporting can sometimes be misleading, with individual opinions elevated to fact status. This is especially true for 24-hour outlets like CNBC and Bloomberg Television. These media companies have a need to tie moves in markets to an immediate reason why something is happening. The reporters sometimes seize on commentators who self-confidently declare to “know” – even though they cannot possibly know all the buyers and sellers in the market, nor all the reasons for the buying and selling. Nevertheless, these opinions get repeated by the news, quickly becoming “fact” and embedded in the evolving narrative.

Regular readers may be becoming almost fed up with our continued discussion of central bank policy, especially that of the US Federal Reserve (Fed). And that’s a useful observation in itself. Are the current market moves really down to the market’s concerns about interest rate policy? Have we (us and the commentators) bought into a narrative, the old rationale now just being a rationalisation? Is there something else going on?

This year has been tumultuous in market terms, for equity markets and especially for bond markets. Focus has centred on the Fed. It has responded to inflation by raising rates, and we (and other commentators) think it will continue to battle against potential inflation. Our own valuation models have done a good job of tying equity and bond prices together and, for a long time this year, the relationship between bonds and equities was in line with our thinking.

However, about three months ago, equities started to diverge and became more expensive than usual, relative to bonds. Of course, our models don’t have all the factors that ‘explain’ prices either. Our thinking was that, in essence, investors were scared of how rapidly the bond markets had been moving back to higher yield levels, with the resulting volatility in the ‘risk-free’ government treasuries valuations having been extraordinary. Equities had been volatile but not substantially more than in other not-so-great- times. Also notable in markets has been relatively low volumes and overall trading liquidity. Market participants seem a lot fewer than usual and, again, especially in the government bond markets.

So, has it been fears about what the Fed will do that has guided the buyers and sellers? Do the buyers and sellers have motivations which we haven’t considered?

Investors are buyers generally because they are savers or acting on behalf of the savers, or in other words are those with excess cash they would like to invest for gainful returns. Investment managers, who wish to act on their behalf, like to think they are rational and therefore will invest according to the macroeconomic and value-based information at hand.

But if end-investors take the money away from them, they will still have to sell something, no matter what the information says. Likewise, if they receive new money to increase investors’ savings with them, it will be invested there and then, regardless of what the managers outlook may be at the time. Thus, the savings rates and flows can be important, and the flows don’t necessarily fit with a rationale.

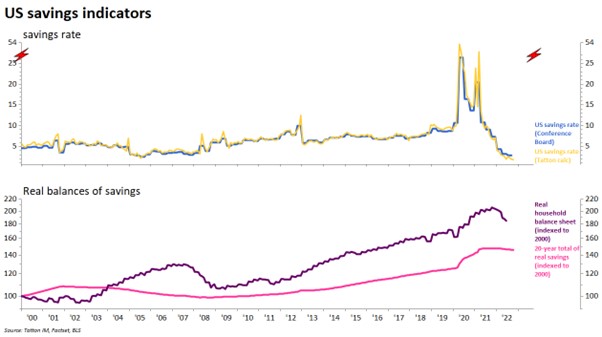

Across the world, and especially in the US, there was an incredible flow of money into savings during 2020 and 2021. At the same time as the Fed was buying bonds to put on its balance sheet, households were receiving cash from the government which they couldn’t spend on what they may have normally spend it on (e.g., holidays) – so they saved it.

The chart above shows the household savings rate (how much of ongoing disposable income is saved rather than spent) and then below is the household balance sheet relative to 20 years of real savings. This year has seen an unprecedented decline in the savings rate. Given the jump in the stock of savings beforehand, maybe that’s not so surprising. Also, if households are sure the price of things will rise substantially but the return on savings will be much less large or certain, they’ll buy things now, rather than saving for later. So, while they may not have taken money away from their savings, the usual flow has been much less apparent. And fund managers had gotten rather used to the idea that the incoming flow would be low.

However, the flow into savings may well have picked up in recent weeks. Surveys of inflation expectations have dropped back marginally but, equally, people seem to be buying less. If they are buying less, they may well be saving more, which means fund managers are having to buy. With low trading volumes and liquidity, as they are typical for this time of year as the seasonal holidays approach, those flows can have quite an impact.

Certainly, in the past two weeks, long-dated bond yields have moved down a lot, as a result of more buyer demand pushing up bond prices. One rationalisation has it that the Fed will ‘pivot’ in its policy of aggressive rate rises, which should make the extent and depth of the central bank- ‘promoted’ economic slowdown/recession less uncertain. Another has it that the Fed will stay hawkish, meaning a greater chance of recession. It may just be ‘a few more buyers than sellers’, for a number of different reasons. Taking a firm view right now on the underlying story might be somewhat spurious and therefore dangerous if it drives decisions.

But there is no denying that the market sentiment has become noticeably more buoyant. While things might change after the new year, when more bond supply may well become available, at Tatton we can see the attitude of savers becoming more positive, which in itself is encouraging.

The Fed’s rate setters (Federal Open Markets Committee) meet on Wednesday for the last time this year, and they will probably agree a 0.5% rate rise to a mid-level of 4.375%. It seems like 2022 has been all about the Fed and it still is, right up to Christmas! Rather than explore the many inconclusive explanations for the sentiment change, we shall wait to hear what the Fed says after its well-flagged rate rise to see how those pronouncements are interpreted before finalising our outlook for 2023. Maybe next year, they will be less important.