Finely balanced

Posted 22 April 2022

Easter week has been a bit mixed for investors – and this was not caused by fears that populist Marine Le Pen closing the gap to incumbent French president Emmanuel Macron may herald another major political upset in the 2nd and final round of the presidential elections this weekend. Nevertheless, at the top level of diversified multi-asset portfolios, the month of April has experienced a relatively mild downdraft from the heights of the recovery at the end of March. Underneath, however, big moves have taken place and some divergences have opened up.

Surprisingly positive corporate sentiment data across Europe this week indicated that consumer demand may not be as significantly impacted by the war in Ukraine as markets had been pricing in. On the other hand, there are signs in the US and the UK that consumers are feeling rather more pressure on their household budgets from rising energy and housing prices than anticipated.

The remarkable moves of the past fortnight have been in the bond markets, where government bonds have sold off to such an extent that real yields (after inflation) of longer maturity bonds are finally at the brink of turning positive. That markets are nevertheless down for the month, tells us that competing views remain in a fine balance. Rising yields have made market valuations relatively more expensive, but this week’s activity appears to focus more on a stagnating sales growth outlook, albeit with not much expectation that an economic slowdown will result in a prolonged recessionary episode. We discuss the two sides of the balance in the next article.

In more fundamental developments this week, we noted that the G20 finance ministers and central bank chiefs in Washington failed to issue a joint communique. US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen also led a partial walkout from a session that featured Russian officials, in protest over their inclusion given Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine. In the current feverish geopolitical climate, the failure may be unsurprising, but it is still significant.

The Group of 20 first met in December 1999 to bring the biggest developed and emerging markets into a single forum to address key global challenges. It was a response to the debt-fuelled capital flight crises of the 1990s; 1994-5 Mexico, 1997 Asia, and 1998 Russia. The last (near) default of Russia, triggered the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management in the autumn of 1998 which very nearly caused a global financial crisis. A globalising world meant the tighter G7, and the looser Bretton Woods system could no longer be enough to maintain stability.

Former US Treasury Secretary Larry Summers was in the Clinton administration throughout many of those 90s-era crises, and is now a Harvard University professor. Before the Washington meeting, on 14 April in Stephanie Flanders’ Bloomberg podcast, he foreshadowed the G20 difficulties. He said that it’s now a “very profound question” as to whether there are enough shared interests in mutual economic development and a determination to jointly solve problems to allow it to continue: “Self-evidently, it is not the objective of most of the other members of the G-20 to support Russia’s economic flourishing… It is a substantial question whether we are hoping for the success of the Chinese economy, and whether China is hoping for the success of our economy.”

Maybe. On Tuesday night, China signalled its dependence on global trade, especially its dependence on the US, by allowing its currency to depreciate. We discuss this and its implications in a separate article below. Chairman Xi Jinping said he firmly opposed “decoupling”, calling for stronger macro-economic coordination. While he implicitly criticised the US and Europe for this decoupling, it is abundantly clear that China needs the West’s demand significantly more than it needs Russia’s raw materials. Xi’s speech could be taken as a cry for help. And while the politicians of Pakistan, Indonesia and Thailand might prefer China’s indifference to the West’s interference in their internal affairs, China’s almost audible creaking shows emerging market nations that they cannot depend on China alone. Not for demand, not for financing.

No matter how much autocratic leaders despise US ‘hegemony’, they must at the end of the day deliver prosperity to their people or risk being replaced. Imran Khan’s removal as leader of Pakistan may be a signal.

The Ukraine war has brought Europe quickly towards the US and now the developed West looks much more cohesive than it did just two months ago. The West’s boundaries of acceptable behaviour being better identified and now policed with sanctions. But as the world appears to be moving to a somewhat weaker overall growth path, the West should be careful not to keep inflicting pain. Away from the harsh words, behind the diplomatic veils, we should want to keep trade flowing and growing. While there is much angst over Europe’s apparent failure to achieve a liberal Russia through expanded trade, we do not have an alternative to this philosophy that is more likely to succeed.

While the current US administration has often appeared no more conciliatory than the previous administration, we cannot know how events would have unfolded if Trump were still President. One suspects there would be even more drama. It would be difficult to imagine that European leaders would be as close to the US if Trump were in place. And the timing in which to rebuild relationships may not be long. The US Presidential electoral cycle will begin even before the midterms, and while Trump has no direct influence on Biden’s policies, it will not be easy to be seen as friendly towards China even though the world might need it.

The recent weakening of the Chinese Renminbi has also weakened the Japanese Yen again, as well as other Asian currencies. Everything else being equal, this might ease Asia financial conditions, especially if bond yields do not rise. But US dollar-strength tends to mean corporate access to US financing gets more restricted and credit spreads (the yield premium paid over the most secure bonds) rise. China corporate spreads have been widening again, which is not surprising given the economy’s weakness. However, there are fewer signs of stress in more specific Japanese indicators such as the ‘cross-currency basis swap’.

The obverse to the weaker Asian currencies is a stronger US dollar. At the margin, that ought to help provide a little bit of help to the US Federal Reserve (Fed) by tightening conditions and reducing some inflation pressure due to falling import prices. However, you would not be able to read such thoughts in recent Fed official pronouncements. Fed official James Bullard intimated he was in favour of more than a 0.5% rate rise next week. The hawkishness was topped off by Fed Chair Jerome Powell giving credence to the idea of a series of 0.5% rises though this year. US short-term rates are now expected to be at 2.5% by the start of 2023.

The good news is that US ten-year bond yields hit a bit of a ceiling at 3% and have eased back since. UK and European yields have also dipped. However, this has not yet helped stocks, which have been reacting more to fears that global growth is facing all manner of headwinds.

In recent weeks, one would have expected rising bond yields and rising corporate credit spreads to have hurt equity prices. However, relative to bonds (real yields) the markets’ valuations were a bit cheap beforehand, so relatively stable earnings projections meant equity markets kept valuations steady as well. Unfortunately, as noted at the start, sales projections are starting to slide, which takes away the equity markets solidity.

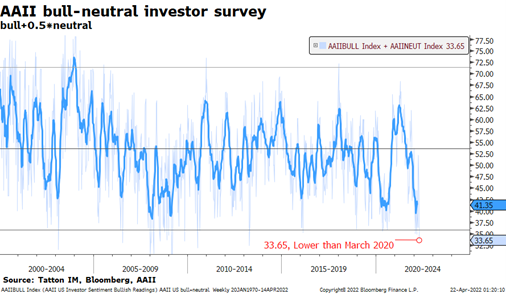

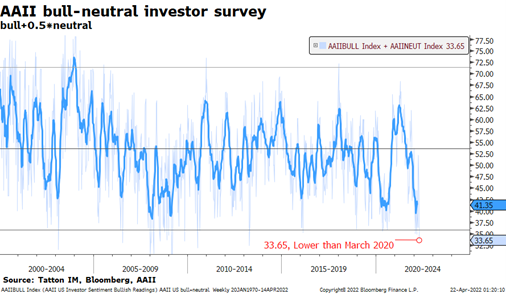

Consequentially, investors have been getting less positive in recent weeks. As John Authers of Bloomberg (formerly with the FT) points out, US investors are as bearish as during the 2008 sell-off.

In itself, this is not a bearish signal. Indeed, some traders see this as a contrarian indicator which might signal a buying opportunity. For us, the weakening growth backdrop is more likely to be important. We are inclined to look through this, given the resilience of the US jobs market and Western households’ still healthy savings.