Football fever saves UK from recession

Posted 13 January 2023

The new year is proving to be a happy one for almost all asset classes and regions. The FTSE 100’s intraday all-time high of 7903.50 is less than 100 points away at the time of writing, and we’re closer than we were last week. The global financial press tell us markets are stronger because we should be positive about a likely easing in monetary policy, and this easing should take place because – as business leaders say – conditions are awful.

And yet things are not that awful, not even here in the UK, where the economy appears to be limping along rather than totally broken down. Today, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that UK gross domestic product (GDP) unexpectedly rose 0.1% in November. Most economists had expected a small decline after growth in October.

According to the ONS, the Qatar World Cup marginally helped consumer-facing businesses and the impact of strikes was not severe. Services growth rose by a better than expected +0.2% on the month, and were also revised up for October. There was little sign of weakening in the jobs market either, as recruitment agencies saw a gain of 2.1%.

However physical production, especially manufacturing, declined more than expected and October’s data were also revised down. The ONS said it could not put an exact figure on the economic cost of industrial action, and the impact is likely to be larger in December when most of the walkouts occurred. But, unless December’s GDP figure falls more than 0.4%, the UK economy should avoid a technical recession in Q4 2022.

As for the impact of strikes, post and rail output fell by 4.7% and 3.1% respectively in November, and this spilled over to a wide range of other sectors, including wholesale trade and jewellery.

The World Cup meant sports activities saw a fall in output as people watched games rather than played them. The strikes didn’t have such a great impact – people went out locally rather than into cities. Strong growth included telecoms and computer programming and social work.

The Bank of England had anticipated a recession was already underway in 2022’s second half, although their monetary policy views are more concerned with supply-side weakness, a problem which it sees lasting into 2024. This morning, Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) member Catherine Mann suggested the data might mean larger rate rises ahead.

The strength of recruitment still tell us that the dynamics that would generate a sharp painful recession may not be evident now, especially as energy prices have been heading downwards. Also, jobs are still available for those looking. That supports consumer spending as fewer people face the nasty shock of a large and sudden cut in income.

On the other hand, the days of large private sector wage rises appear behind us, with the likes of Amazon taking action to manage its warehouses – shutting venues where labour is expensive and difficult to find, while opening new ones where labour is more plentiful.

Yes, the strikes continue and look likely to get worse. However, even if public sector pay rises are awarded, it was a figuratively bloody battle to get them. Eventually, there will probably have to be some compromise from the government, but the cost of fighting means that a wage spiral is unlikely to take hold. Thus, pay rises are slowing even though there is no big upswing in the unemployment rate.

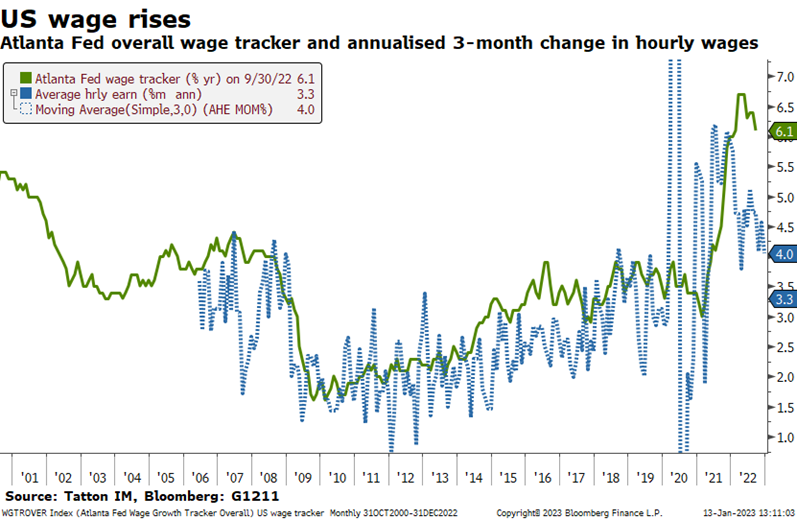

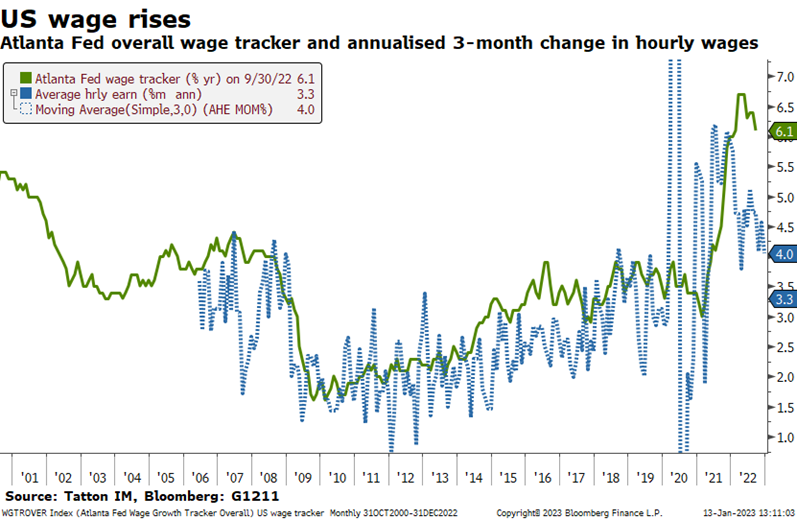

Across the pond, members of the US Federal Open Markets Committee (the equivalent to the UK’s MPC) were also vocal that rates are still going up, although US bond investors believe the rate rises are nearly done. The slowing of wage rises is also apparent, as the average hourly earnings data showed in last week’s nonfarm payrolls.

At the same time, few investors appear to believe a US recession is about to take hold. The bond market also tells us that fears of defaults in the credit market are declining, and that’s a stronger indicator of recession fear than the much-commented yield curve inversion.

When J.P. Morgan released its 2022 Q4 results today, its Chief Financial Officer Jeremy Barnum said it was still hiring and in growth mode. Indeed, his company will be happy that this week has seen a massive splurge of bond issues across the world, given that the going was very slow for investment banks at the end of 2022. As mentioned last week, issuers were sidelined for much of last year while investors were building up cash. The first two weeks of January have been incredibly busy, with huge new issuance being met by “huger” investor demand. On Wednesday, Bloomberg reported: “Demand for Europe’s debt sales has topped half a trillion euros already this year as investors seek to put money to work in bonds offering some of the highest yields in years. Investors have bid €530 billion, more than three times the €168 billion of issuance in Europe’s syndicated primary market so far this month”.

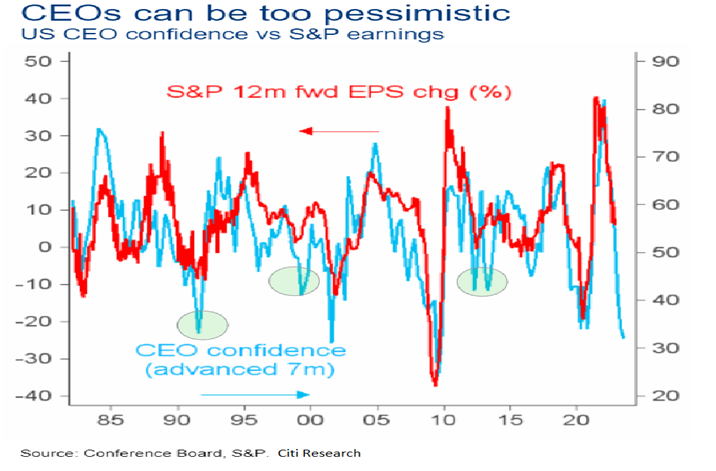

The US earnings season gets into full swing next week. Given the very pessimistic results of the various business surveys, one would think that these will be especially dire. However, so far it hasn’t been too bad, and the large American banks have not been too downbeat (Matt King of Citi Research points out that business leaders can be too pessimistic):

The direct measurements of economic activity have been weakish, and December’s data is yet to be released in full. However, the ‘soft’ survey data, which tends to lead the ‘hard’ direct data, has been suggesting more weakness than has happened. And, indeed, the surveys in Europe and Asia shows signs of getting less pessimistic.

Certainly, the fear that the world was close some sort of economic precipice seems to have dwindled significantly. Investors may already be discounting a rosier picture, one where the nasty risks of 2022 seem to have ebbed quickly away. But the central bankers may need some convincing that a wage-price spiral is no longer a danger, given that as yet there is only the mildest of hints that the pressure has eased.

We’ve had two weeks of ‘bad news is good news’ helping the markets. For markets to go higher in the long-term, let’s hope we have a run of ‘good news is good news’.