Market wrestling

Posted 10 March 2023

Tatton Investment Management Limited is still a young company but we are getting a little older. This year, we are proud to celebrate ten years of serving our clients and are immensely proud of what we have been allowed to achieve for portfolio investors and are grateful for the trust shown in us.

The company is young but we, the individuals charged with making investment decisions, have to admit to being quite a bit older. Some of us even started before the “Big Bang” of 1987! It has the advantage that the déjà vu of inflation-affected markets isn’t just a sense, it really is déjà vu.

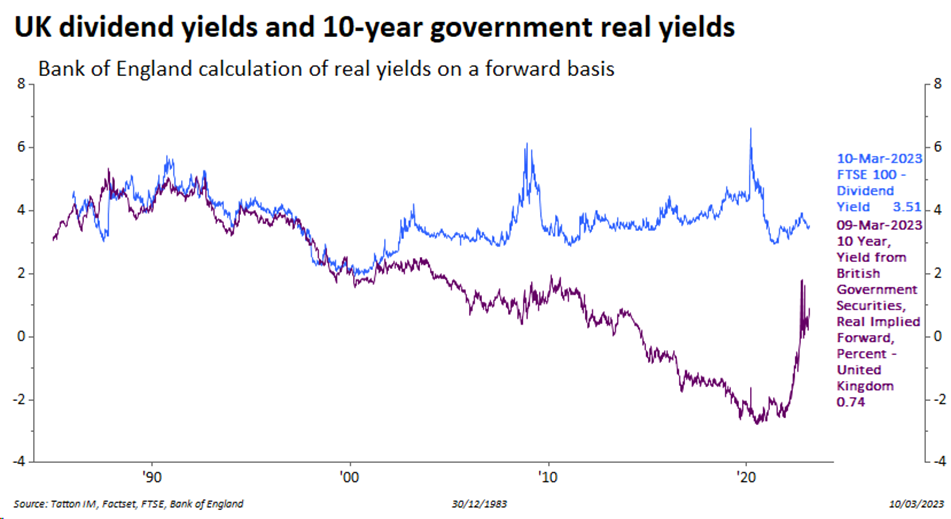

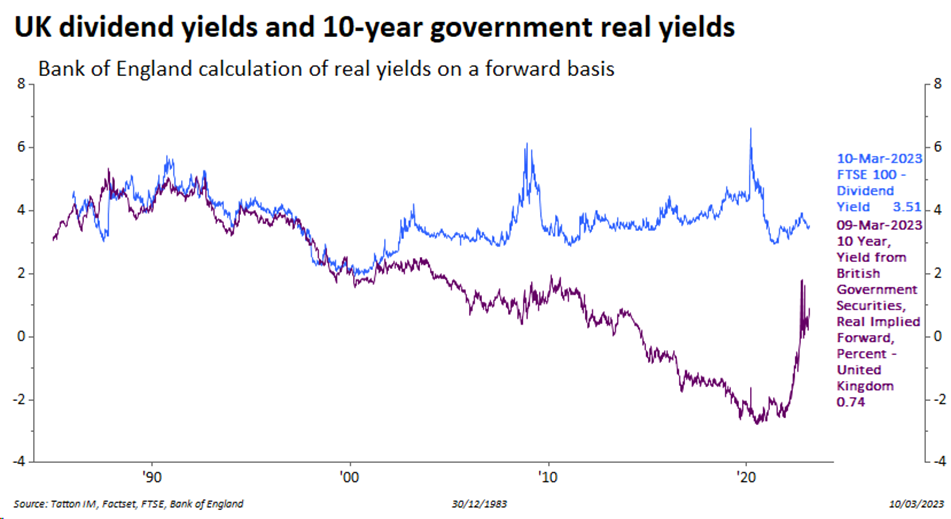

For weeks we have been talking of an equity market that is relatively expensive in comparison to bond markets, especially government bond markets. Below is a chart which tracks the dividend yield of the FTSE 100 (calculated from 12-month trailing dividends) together with the market-estimated real return (after inflation has been subtracted) of the 10-year gilt calculated by the BoE. It is reasonable to think of dividend yields as an inflation-adjusted (or real) yield given that companies pay dividends out of profits which are made after inflation-affected input costs.

Importantly, over the long-term, dividend growth will be in line with earnings growth and that is usually in line with nominal economic growth. It will outstrip the growth in retail prices.

If we were to start this chart just five years ago, we would see a decline in dividend yields and a sharp rise in government real yields. One could expect dividend yields to rise to maintain the premium, and that would in the short-term mostly be achieved through lower equity prices – which hurts capital values. But over the period from 1986 to the start of this century, the relationship looks completely different. Dividend returns from stocks were in line with real yields from government bonds, except that equity investors got the growth in the value of the stocks on top. The two periods are very different and, certainly, there are reasons to think that the 20th century relationship could return. While from dividend yield perspective equities are on the expensive side, they are not expensive relative to government bond yields in a wider historical context.

Valuation arguments are never the best guide to short-term stock market performance. However, valuations often guide how professional investors position between asset classes over the shorter term. In various discussions this week, we heard market participants telling us how expensive they consider equities and high yield bonds in relation to the current risks to expected earnings and corporate default levels this year. This backs up the gauges of market sentiment published by researchers like Bank of America which show how equity market bearishness among institutional investors has been quite high and for quite a long period.

US investment bank Morgan Stanley has noted the discrepancy between institutional investor risk-off positioning and actual market resilience this year. As a result, it has – as of Monday – altered its short-term investment view back to bullish (as it did last autumn before the last rally) anticipating stock markets could start to rise despite their longer-term bearish outlook.

Morgan Stanley has a point, given many investors are at risk of underperforming their benchmarks because they are weighted towards cash. Being out of the market for an extended period makes those active institutional investors twitchy, so they tend to jump the other way on any sign that market action is not aligning with their expectations – particularly as each (reporting) quarter comes to an end. Our conversations make us also think that being underweight equities is a ‘crowded’ trade. As we head towards the new tax year, there may be a tendency to want to move back to neutral.

But, of course, we should also acknowledge that there are many good reasons for investors to be fearful given profits might face a tough time during the rest of the year, which may eventually undermine the enthusiasm of the cohorts of casual investors who are perhaps not as driven by economic data analysis. We write below about the expectations for rate rises in the UK, in Europe and the US over the next two weeks. Compared to a month ago, most investors expect rates to be quite a bit higher by the summer. Of course, this is because economic growth has been more resilient, which should help this quarter’s profits to be better than expected.

Nevertheless, those higher rates will stress some weaker companies and more will default than otherwise. For the broad markets, the question then becomes whether this process becomes disruptive for the whole economy, which is when risks shift from being ‘idiosyncratic’ (company specific) to being ‘systemic’. In this context, the most dangerous times are when banks are on the brink.

The news this week that California-based Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) had gotten into difficulties gave the markets a big wobble and might have caused the opposite to what Morgan Stanley was basing its short-term change of strategy on, namely a larger number of investors got a fright that the economy may not after all pull through largely unscathed. We note in the article below that US Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell’s testimony to Congress changed his tone from quite hawkish to somewhat more diffident between Tuesday and Wednesday. We can assume he would have been informed of SVB’s cash call before Thursday’s announcement.

SVB is part of a group of companies large enough to be in the S&P 500, so it isn’t small. It seems to have been caught up in the cryptocurrency travails after its crypto unit, Silvergate, was shut out of the market. At the same time, SVB is not noted for being a large lender, so it is not likely to be significant in providing liquidity finance to companies and thus being systemically important for the US economy.

Even though SVB’s troubles appear entirely idiosyncratic, banks across the board were hit hard this week after a good run this year. Investors will be trying to judge whether banks are still a good thing given the general rise in rates and yields is known to be beneficial for profits, but the negative yield spread between what they have to pay deposit holders (short maturities) and what they receive for longer-term loans is not. Should higher overall yields lead to non-performing loans suddenly ballooning this all has the potential to turn a positive sector story into quite the opposite. We have been somewhat surprised by this ‘sudden’ insight in markets, given the negative yield curve spread has persisted for some months now (and so have higher lending costs for businesses). It seems sometimes that many of todays’ capital market actors still have to get their heads around the dynamics that high yields and higher rates of inflation bring with them.

The Fed’s judgement on this seemingly outsized market reaction will be important as it will undoubtedly affect views on future rate moves. Its members have now moved into the pre-meeting quiet period but that only applies to the rate-setting committee, so there may still be information flowing from the Financial Stability section.

Looking back at previous bouts of rate tightening, they have happened before and one should not over-estimate the immediate impact of such episodes. Equally, this week’s events signal that stress is starting to be revealed – a domino has fallen and others might well get knocked over.

Still, the Fed’s rate-setters will also look at another economic news items of this week and may note that the jobs market remains astoundingly strong and wonder when the weakness of Californian tech-related entities will mean an easing in the labour market.

For the first time in what seems a very long time we have had a week where government bond prices have risen while equity prices have fallen. Equities initially would be supported on the valuation side by the fall in yields (the opposite of what happened last year, when yields rose and rose) but the concern that crept in this week is: when will it be more important if profit forecasts are downgraded because of emerging stresses. Certainly, it is possible that these first cracks in the wider credit markets have increased the systemic risk level, and much will depend on the views of the (somewhat unknown) group of risk overweight investors over the coming week. For the moment, they seem to be more inclined to hold on to their conviction of inflation-beating longer-term returns from equities and look beyond the shorter-term pain of stagnating and temporarily falling corporate earnings. We feel the coming weeks will prove quite insightful for us with regards to which of the market sentiment sides will succeed in this year’s market wrestle.