Markets hit a bit of to and fro

Posted 20 August 2021

Markets hit a bit of to and fro

Investors would be forgiven to think that this week’s downdraft in global stock markets was in reaction to the rapid unfolding of the tragic events in Kabul, Afghanistan. However, as long-time observers of risk asset markets will attest, unless human tragedies are likely to have a discernible impact on the global economy, stock markets do not show any empathy to present or foreseeable human suffering.

The fact that global equity and commodity markets gave back this week most of what they had gained since the beginning of the month was driven by a combination of bearish headlines about the COVID-19 Delta variant and economic data continuing to disappoint after the exceptionally strong June figures. In the words of our economists, the economic recovery has hit an ‘air-pocket’ – doubts over the further sustainability of the recovery are creeping in, while fiscal bridging support is being phased out without structural fiscal infrastructure programmes having yet begun.

Overall though, we believe supply chain difficulties are the major driver of the slowdown. So it would be tempting to think the unfulfilled demand will remain just that, pent up until the supply comes along. The trouble is that everything is circular (which is really the point of classical economics); demand affects supply affects demand affects supply, and so on.

If workers in a car factory are stood down because there are no semiconductor chip deliveries, they will feel comfortable with a day’s lay-off, even a week. Beyond that, they will be increasingly uncomfortable about the ongoing security of their jobs and income.

If the chips are delivered at half the previous pace, and at twice the price, the car company may want to raise its prices. Demand was strong three months ago, but now workers are feeling less secure (especially their own) and not so ready to spend, especially if the cars are now more expensive.

Shocks and adjustments are basic economics (the supply-demand curves, originally applied to asset prices and the availability of loans by Maynard-Keynes). The conclusion that a sustained supply shock results in higher prices and less demand is unsurprising, so why are economists seemingly so surprised about the weakness now? It is probably because this is a supply shock which is of an unprecedented nature.

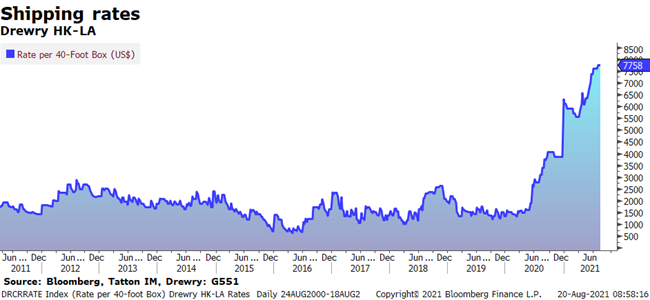

Not the usual regional affair, but instead a global shock in a globalised world. It has continued for longer than most had bargained for, even if the virus’ public health impact has being much reduced by vaccinations. And now COVID-19 has swung back to where it started – Asia. The renewed regional lockdowns there may be partial but they are hitting South-East Asian manufacturing and shipping yet again, as out-going deliveries should peak for the winter holiday season.

Yesterday Bloomberg reported a partial shutdown at the world’s third-busiest port in China, which risks further disrupting global supply chains and maritime trade. Bloomberg suggests congestion is up about 60% at the ports of Xiamen and Shainghai/Ningbo in China. Shanghai, Zhejiang province to the south and Jiangsu to the north are all large manufacturing hubs, the Yangtze delta being a major gateway for goods to the rest of the world. Factories there produce auto parts, electronic modules and chemicals used in various industries.

With continued pressure on shipping prices, it may seem odd that the week’s European-wide consumer price inflation (CPI) data surprised by being lower than expected, and the UK is providing a good example of what is happening in the wider world. For example, July CPI was 2% year-on-year, well below the June reading of 2.5% and the expectations of around 2.3%. Some of the decline in the rate-of-change can be ascribed to the basic math of ‘base effects’, which implies the readings should decline after a sharp rise in price levels in the second quarter.

However, retail sales also tell a story of price rises eating into both spending power and consumer confidence. By volume, overall retail sales dropped back by about 2.5% from June, whereas consensus was for it to be unchanged. And the GfK consumer confidence indicator dropped back relative to the previous month, the first decline since January.

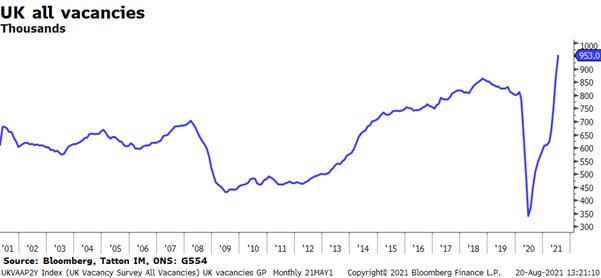

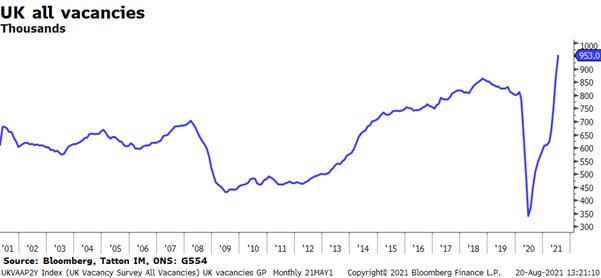

Of course, the adjustment processes go in phases. So, under most scenarios, it is likely the supply disruption will probably be over before jobs are actually at risk. That is partly because employers have been reminded that finding workers is difficult, as UK jobs data continues to show. Indeed, part of the supply chain disruption is down to that very fact. The payroll data showed a strong July increase in employees of 182,000. Job vacancies have also been climbing as the chart below shows:

But for stock markets, we have hit an uncomfortable point. Confidence over growth remains strong, but the timeline for when this growth happens is being pushed out again. That means corporate earnings estimates for this year (and probably for next year) are going to be under pressure. Analyst estimates have just been through the usual review process after the very strong first half results, but now it is quite likely they will be pulled back – with some of this again being driven by the base effect. Relative to where real yields in fixed interest bond markets are, equity market valuations are not expensive. They could even be said to have become cheap as earnings rose but yields came down over the past months. However, when earnings expectations decline, this can change quickly, meaning equity markets could have a bumpy ride, as we have seen this week.

The good news is that economic data also tells us the current demand adjustment to the supply disruptions should be just that: an adjustment, not a shock in itself. This week’s UK employment figures showing almost one million job vacancies in July also tell us that the discomfort of temporary supply shortage-induced lay-offs may be far more limited than usual, which should further reduce the risk of the economic cyclicality dynamics mentioned at the beginning. In other words, as long as the supply constraint dissipates reasonably soon, we should resume the upward path later, and with markets cheap enough to benefit.