Plugging the holes

Posted 18 November 2022

The Autumn Statement, budget-in-all-but-name, had been sign posted as very likely to bring bad news to UK taxpayers, as the third Conservative government of this parliament changed course from Trussonomics back to Rishinomics. As we had suspected in our video update this week, what was announced in the end was less bad than what had been leaked beforehand, which is how bad news tend to be sold. With fiscal responsibility returning to the UK, and with it a certain predictability in policymaking, this Autumn ‘budget’ was perceived as quite sensible from a capital market perspective with sterling and bond yields closing within their most recent trading ranges.

But while this Autumn Statement was intended to allay concerns of both capital markets and voters, the wider public was more focused on tax increases. For now, it seems Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has managed to keep foreign buyers of UK government bonds onside, while maintaining the enormous fiscal expansion of the energy price cap but pushing the bulk of the tax rises and spending cuts into the next parliament in 2024 and beyond. So, it appears this Autumn Statement amounts to no more than a short-term repair job rather than a long-term strategy to overcome the UK’s structural weakness of comparatively low productivity caused by the lack of capital and education investment paired with Brexit-curtailed trade opportunities.

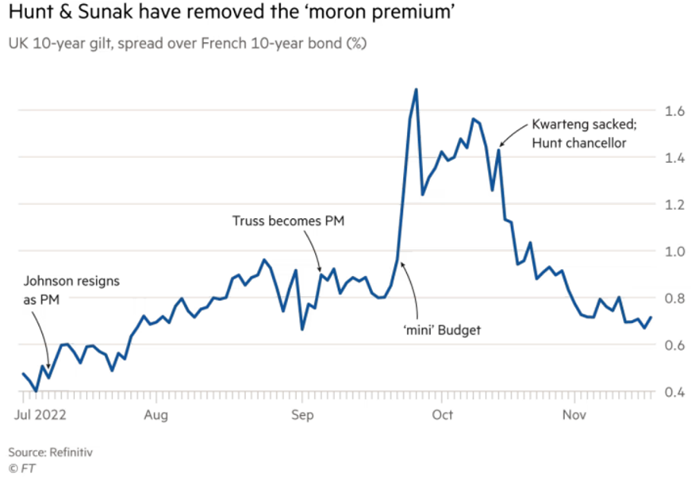

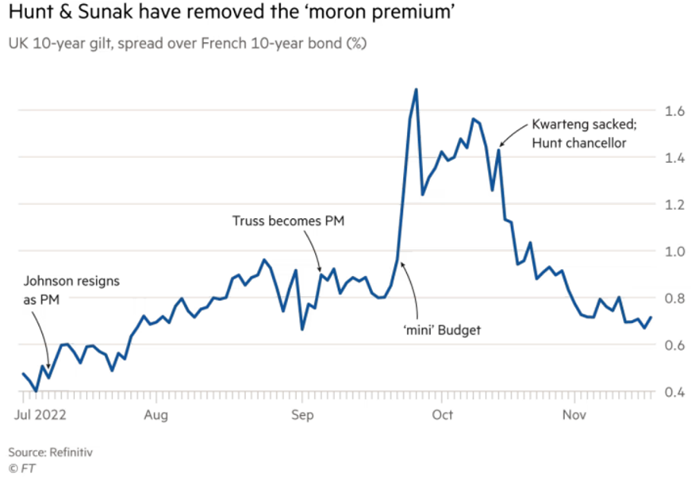

The chart below shows that the worst of the yield scare for British mortgages and the wider property market has been neutralised since Hunt was appointed, but should the dire Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) forecasts become reality, UK households will be faced with the inevitability of shrinking real incomes for years to come. No wonder the shadow Chancellor called the postponement of the brunt of the tax rises and public spending cuts an election ‘trap’. Luckily the OBR report also contained a few lifelines for UK wage earners, such as the prospect that inflation may well turn negative in 2024 and pull down yields with it. Given the recent steep fall in European gas and electricity prices, the energy cost price shock may also end sooner, thereby lowering the upward pressure on energy-intensive goods.

While the UK public was focused on the Autumn Statement, and despaired over the latest inflation data, the most significant news in the global investment world once again came from China. Following the display of dogmatic inflexibility at the Communist Party congress a few weeks ago, President Xi presented a far more cooperative version of his leadership at the G20 summit in Bali, where he not only met many of the western leaders one-on-one, but also supported some harsh condemnations of Russia’s Putin. Investors had only just been declaring China as un-investable, responding to Xi’s power show with an up to 20% stock market drop over October. However, investment has flowed back since the beginning of November, leading to a surprise recovery reminding investors that China is still an economic power they can ill afford to ignore. In a separate article this week, we discuss how other meaningful adjustments around China’s zero-Covid policy – and its property market – led to this pivot in investor sentiment over at least the shorter term.

Speaking of un-investable, the latest crypto-currency crisis has turned crypto currency exchange platforms into just that. As we learned about ‘warm’ and ‘cold’ crypto wallets, it has become ever clearer that the world of crypto is just as corruptible in the absence of regulation and oversight as conventional hard currency markets. There are fears that losses suffered by the crypto trading public amounting to tens of billions of dollars may cause a broader liquidity squeeze in the non-crypto world. However, the underlying issue here is that crypto-currency assets have been used as collateral among other crypto institutions and some hedge funds. Therefore, it is far more likely that the fallout from this particular crisis will ultimately bear more similarities with the deflation of the 2000 dotcom bubble – albeit at a much smaller scale – rather than a more systemic threat to the broader capital markets.

On the whole, investors enjoyed another positive week in markets, as better-than-expected US retail spending figures, a falling dollar and still-declining European energy prices prolonged last week’s positive sentiment swing initiated by slowing US inflation. The trouble with this is that all these data points indicate more current and future resilience in the US economy and a potentially shallower recession in Europe. This is not providing central banks with the necessary confidence that the labour supply pressures in the inflation equation are likely to ease any time soon. As a result, a near-term pivot in their monetary policy away from tightening is no more likely now than it was a month ago.

The improvement in stock market valuations over recent weeks has been entirely due to the improvement of valuation metrics from the decline in yields in anticipation of such a policy pivot, while the wider corporate earnings outlook has continued to deteriorate. The December meeting of the US Federal Reserve rate setters will be awaited with a fair dose of nervousness, and anything less than a clear signal of a pivot is likely to lead to significant market disappointment.