Public sentiment vs economic realities

Posted 24 June 2022

Through much of this second quarter, the financial market narrative has been about inflation. This week the Office for National Statistics (ONS) informed us that inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose from 9% in April to 9.1% in May, while the Retail Price Index (RPI) rose 11.7% compared to May 2021. UK inflation-linked benefits for 2023 – including pensions – will be determined by September’s data sets, and means the state pension will almost certainly increase by more than 10%. This will make it increasingly difficult to hold down further pay demands, especially in the public sector. The UK data follows on from the US May CPI data which precipitated the 0.75% rise in US rates.

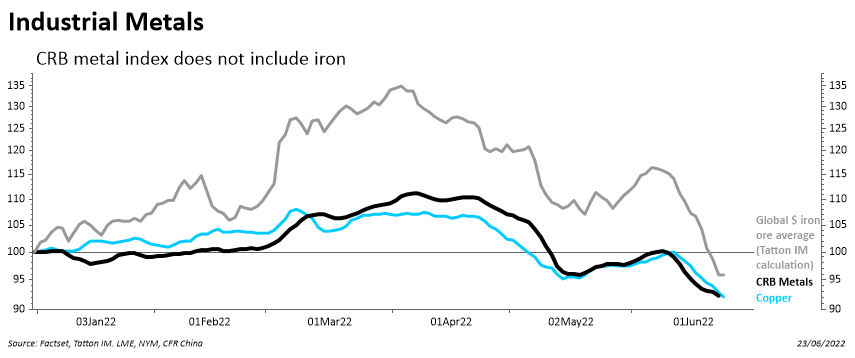

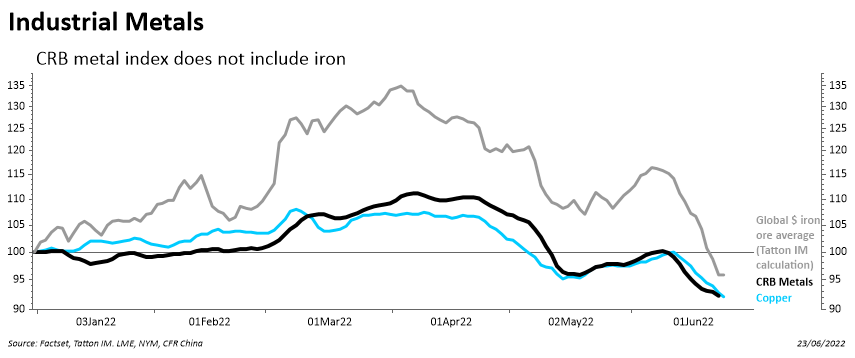

And yet, signs continue to indicate that the global supply-chain squeeze is abating, and the cost-push is passing by. As the chart below shows, having peaked at the start of the second quarter, the average prices for industrial metals are now below the price of the start of the year.

Energy prices have been stickier (especially in Europe) but crude oil prices came down sharply this week. Perhaps most hearteningly, there has also been a broad-based decline in agriculture prices since peaking around mid-May.

The downside to all of the good news is that it is accompanied by a bad-news narrative: “commodity prices are down because growth is weak”. Thursday’s initial (flash) Purchasing Manager Indices (PMIs) for major areas added to the gloom – showing a greater decline in optimism among businesses than economists forecasted one week ago. Composite PMIs were soft across the board, especially for the Eurozone. S&P Global reported that new orders for goods and services “stagnated, failing to rise for the first time since the recovery of demand began in March 2021”.

Such a narrative is not surprising. The follow though of inflation sees people deciding they don’t want to pay the price for goods, thereby reducing demand, and that means less activity and so less growth. The phrase “demand destruction” means exactly that.

On Thursday, Bloomberg reported that US Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair Jerome Powell called his commitment to curbing inflation “unconditional”, while another of his Fed colleagues backed raising interest rates by 75 basis points again in July, even as Democrats warned the Fed against triggering a recession. During his second day of semi-annual congressional testimony, Powell told the House Financial Services Committee: “We have a labour market that is sort of unsustainably hot and we’re very far from our inflation target” and that “We really need to restore price stability, get inflation back down to 2%, because without that we’re not going to be able to have a sustained period of maximum employment”.

That tough talk may be what’s needed to constrain spending, but the bond market now believes central banks will have finished hiking by early next year, and the expected peak in US interest rates will be lower than thought one week ago, down from 4% to 3.5%.

Is a global recession inevitable? Possibly. There is undoubtedly a slowdown underway now. There are two leading indicators, quite separate in their type, which suggest difficult times ahead.

The first is the US dollar monetary base, which has fallen back sharply. This may sound arcane but is drawing attention from many institutional investors. We’ll discuss this in more depth next week.

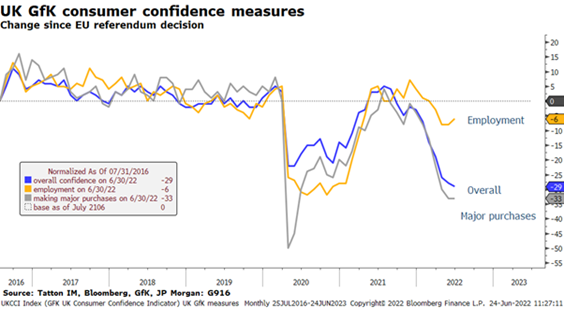

Consumer confidence measures are more relatable to company profits, and the collapse in many regional measures has been striking. As an example, today’s UK GfK consumer confidence measure shows confidence has never been lower in its 49-year history, setting a new low for the second consecutive month, although employment sentiment improved slightly from May. We see a similar situation in other regions such as the US. (Thanks to Allan Monks of JP Morgan).

Business confidence has deteriorated from very positive levels, but is still at neutral rather than negative. While employment may worsen (it does lag confidence measures), it is unlikely to contract massively unless there is another shock to the global economy. There has been a slowing in hiring but jobs cuts are few and far between just now, and employers will be reluctant to lose workers again, given how difficult it has been to recruit in the past two years.

There is also another possible reason for optimism. Market commentators have generally ascribed the fall in commodity prices to a lack of demand, supposedly centred on a weak Chinese economy. However, there could well be another factor in this – Russia. China and others who are less concerned with the morals or politics of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have quickly been sourcing supplies of raw materials. We’ve seen estimates that China has been able to get the discounts for oil of about 30% and, according to Bloomberg, 55% of current supply is coming from Russia, up from about 30% last year.

Several indicators are showing China is rebounding after the COVID lockdowns. China’s economy has clearly been weak this year, but stock markets have shown stability – even strength – while the rest of the world has been languishing. Beijing may not be pumping-in massive amounts of liquidity, but the Shanghai interbank three-month rate is down at 2% from 2.5% at the beginning of this year, meaning the People’s Bank of China is cutting rates while the rest of the world raises them. China’s continued trade with Russia may sustain Putin’s war effort and heighten the chances of enforcing an energy squeeze on Europe. However, many will be relieved if the supply side of the world’s economy shows signs of getting less tight.

Therefore, the sequencing of the slowdown is important. The fallback in input cost-price pressures is welcome and, clearly, it’s a good thing that this is happening before firms have to set about cutting labour costs. This must lessen the chance that the slowdown will be prolonged.

What’s more, central banks are only partially through their rate cycle, and they still have some degree of flexibility. They don’t have to tighten if they believe cost pressures are abating enough – they just have to convince markets that they will do what is necessary.

Lastly, another source of optimism is likely to come through as we head into July. The Q2 earnings season should see reasonable profit growth. After a lot of downbeat forward guidance from firms that have been feeling the pinch, hopefully the reports will be a bit more upbeat.

So, in summary, there are positive aspects in the currently overwhelmingly negative media coverage. Markets are – once again – climbing the wall of worry and that is likely to persist through the summer. This doesn’t feel like a positive, but a slowdown was inevitable. Previously we wanted to hear that central banks would do “what it takes” to control inflation. Now investors want them to be flexible enough not to overdo it.

It seems to us that rather than worrying about being in a technical recession or not, we can expect the downturn to generate static global profit growth through the rest of the year before resuming a normal upward path through 2023. We cannot expect a meaningful equity market recovery until the soft patch is likely to end but, equally, the likely payoff is high enough to stay invested. We will be watching and assessing changes as intently as ever over the summer months.