Q2 begins with QT top of the agenda

Posted 8 April 2022

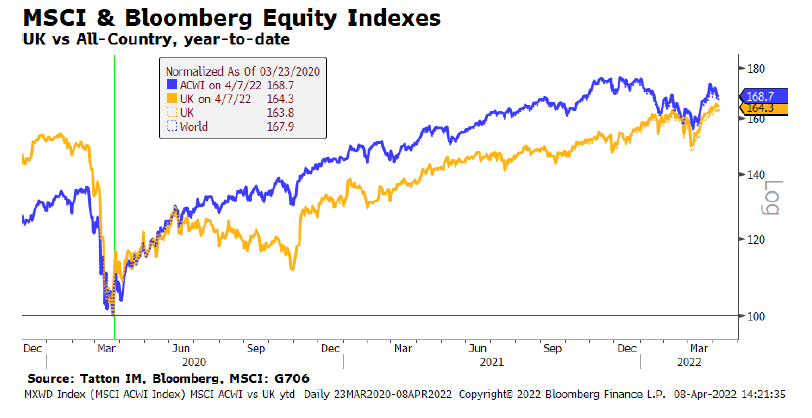

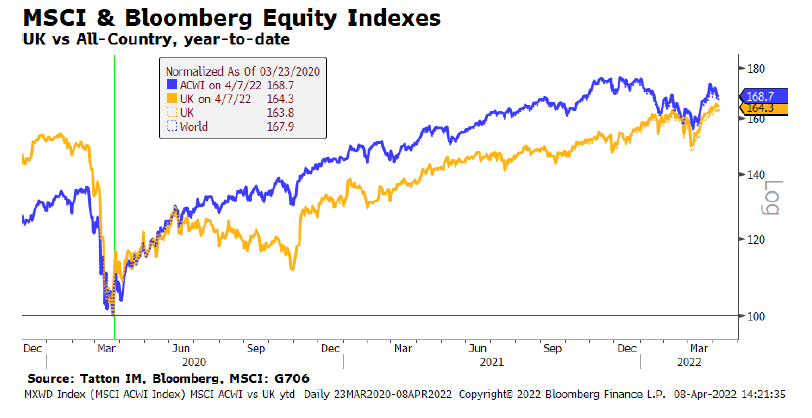

Claire Bennison, our esteemed investment colleague and chart guru, has been talking of global equity market consolidation for several weeks. The chart below shows global equity and UK equity total return indices from the onset of the pandemic to now.

In aggregate, global markets have managed a decent enough bounce since the onset of Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Indeed, the awfulness of the news from the area has ceased to impact markets greatly. We have returned to worrying about the resurgence of COVID-19 in China, along with its impacts on the global supply chain and on overall global growth, and worrying about the US Federal Reserve (Fed) and its plans for tightening US monetary policy.

Indeed, more than a month after the onset of hostilities, the ‘hard’ economic data has been on the positive side of expectations. Although confidence measures have taken a hit, mostly because of fears about inflation impacts, spending remains robust. March data showed the biggest monthly rise in US unsecured consumer credit, up a startling 11.3%. Meanwhile, there appears to be little impact on jobs. As long as this continues, company nominal earnings growth should remain positive. Looking at the track of analyst expectations into the Q1 reporting season, we note that margins were pulled back a bit, but revenue growth is expected to be robust. Thus, overall earnings expectations continue to be revised up marginally. Europe is faring less well, as one might expect, but has more pessimism built in.

When earnings rise, markets generally have a good time. However, valuations are under pressure because of a sharp rise in global government bond yields. The Fed and other central banks have been telling us for some time that we should expect rate rises and so the bond market has factored this into their valuations. We have an article below which looks at some of the aspects of yield levels.

This week however, the Fed signalled how it intends to reduce its balance sheet. In the minutes of its most recent meeting, quantitative tightening (QT) was much talked about. The Fed plans to run down its $9 trillion balance by around $95 billion per month.

At the same time, little consensus has emerged about the impact of QT on financial markets. The announcement effect is generally seen as less powerful than when a splurge of liquidity is in the coming in the form of quantitative easing (QE), when the Fed buys debt in the market. At the same time, ten-year government bond yields have certainly been rising over the past couple of months, but it is unclear whether this is on the back of expected higher policy interest rates or QT.

There are a couple of stylised statements we can make, though. QT is hardly going to be a positive for financial asset prices. Of course, other positive factors, such as earnings momentum, can still mean that overall, financial markets stay in a positive mode. Nevertheless, in a cyclical set-up, QT will likely oscillate between being a neutral to negative factor. The longer QT lasts, the more liquidity gets drained from the financial system, and the more likely this is going to be negative. Structurally, some may even argue QT is needed to connect financial assets more with their fundamentals.

Other observers point to the flow effect of QT. The Fed will not be buying up debt anymore, therefore not only is the marginal buyer absent in the form of a price finding mechanism, but no new liquidity is being created to keep the system running smoothly. Here, matters (unfortunately) become a bit complicated in the current QT episode in the US. So much liquidity has been created, such that the Fed had to mop it up in form of reverse repos since last summer. It is parked in reverse repos, which in aggregate are worth close to $2 trillion.

So, there is the possibility that as the Fed shrink its balance sheet, the actual withdrawal of liquidity gets buffered by current excess liquidity being released back into the market. Much will depend on how the Fed sets interest rates on various deposit schemes that current market participants have with the Fed. We expect that more insight will arrive in May, when the Fed is expected to formally announce QT.

Meanwhile, the competing currents of earnings and interest rates are probably behind the consolidation that Claire talks about.

Although the FTSE 100 is yet to achieve the highest price of 7903.5 seen on 25 May 2018, the total return index (which includes the effect of reinvesting net dividends) went past that level decisively at the start of last October. Global equity indices (best represented by both the MSCI All-Country Index and the Bloomberg World Index), have outperformed the UK over that period, by about 30%, and by about 37% since the Brexit referendum. However, from the low point when the pandemic dragged equity markets to their nadir of February 2020, the UK’s underperformance is now less than 3%.

Since the start of this year, rising metal and energy prices have benefitted UK stock prices substantially. With Shell, BP, Glencore, Rio Tinto and Anglo-American all in the top 10 of market capitalisation, the UK market has more in common with some emerging markets than the US and Europe. We write about winners and losers in the emerging markets in another article below.

However, last month, the commodity-related sectors trod water, while AstraZeneca stormed ahead after its results showed substantial research and development (R&D) success. It now tops the market cap list, with a weight in the index of 8.25%, just ahead of the combined Shell stocks. Concentration in the larger caps continues, with 50% of the index now in 11 stocks, down from 13 in 2018.

One aspect of the UK’s performance is a sense that its most representative index has little to do with the domestic economy. Of the top 11 companies, none have substantial revenue exposure to the UK. The first and most UK-exposed is Lloyds Bank (15th with a 1.6% weight).

Lastly, this weekend sees the first vote in the French election. Mark Dowding, Chief Investment Officer of Bluebay Asset Management, and an old friend tells us “Le Pen has been making notable gains at the expense of Macron on the issue of inflation which, rather than Ukraine and any looming security threat, is the dominant issue on voters’ minds. A narrowing of polls suggests the probability of Le Pen winning in the second round run-off on 24 April could be as high as 20%. Macron is still likely to prevail, but this election is closer than previously envisaged.”

He sees an outside possibility of renewed EU fragmentation risks which could put the ECB in a difficult position. However, even if Macron does prevail, Mark senses a building division within the European Central Bank Governing Council (and we agree). The consensus which built after the eurozone crisis may be falling apart, and that could cause bond yields to head higher, especially for the periphery nations.