Rising yields are back

Posted 1 October 2021

The energy bottlenecks we wrote about last week became rather more personal for the large proportion of the UK population that are motorists. In fairness, the UK’s petrol station forecourt crisis has little to do with rising energy prices around the world, but with a more specific shortage of heavy goods vehicle (HGV) drivers, combined with the population’s dwindling trust of UK institutions to foresee and resolve issues before they occur. This collective mistrust triggers the panic buying response, rather like with the toilet paper shortage of last year

Source: Christian Adams, 29 Sep 2021

Nevertheless, a shortage of gas and oil around the globe leading to rising energy prices had commentators quick to drawing parallels with the 1970s oil shock. This was one source of debate amongst investors over the course of the week. More important, though, was that the topic of rising yields, which was making a comeback from Q1 of this year. This time, however, the narrative among equity investors was opposite. This time the reason cited for rising yields was not growth overheating, but the spectre of stagflation. As a result, stock markets ended September in just as unhappy a mood as they had been throughout the month.

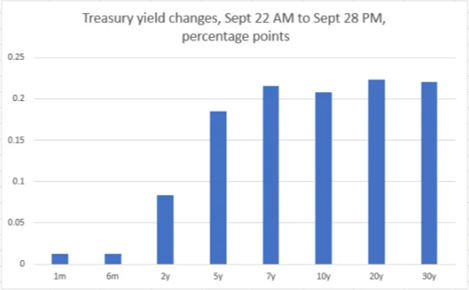

This conclusion – fears of a faltering economic recovery due to more and more supply bottlenecks coupled with rising prices leading to persistent higher inflation – is understandable given the personal experiences of the week. However, the bond market movements of the past week suggested quite a different narrative, namely that the rise of longer-term bond yields, rather than shorter ones (see chart below) confirms expectations of continued economic growth as expressed by central bank statements last week, while inflation pressure are seen as transitory.

Source: FT, 29 Sep 2021

Regardless, as we have noted here before, rising yields are seldom greeted positively by equity markets, so the month closed on a low for investors. Congruently with the bond markets though, the more yield-sensitive growth and tech sectors suffered more, while the long-unloved energy and cyclical value sectors fared relatively well.

So, despite the gloomy crisis talk, and stock markets having given back most of what they gained over August, the overall message was not an entirely negative one. The cyclical recovery is on track and with it a gradual upward normalisation of yields – even if there may be a bit of a hiatus over the coming months as supply issues need to be resolved. Just as has been seen on the petrol garage forecourts, higher energy prices will dampen some of the joy of consumers returning to ‘normal’ public life and resumption of travel opportunities.

Significant factors in how well (or mediocre) the medium-term upswing turns out to be will include any changes in real earnings of the workforce (labour) and the extent to which business investment further reinforces demand and increases productivity levels in response to labour shortages. We cover this aspect in more detail in a separate article this week.

The other big story of the week was the German general election. As we anticipated, it did not turn into a market-moving event, despite the 16-year incumbent party losing out, after Angela Merkel decided to retire (the first time a sitting chancellor did not run again). The German electorate unequivocally voted for change, even though in a very German way: orderly and not too much change at once, please.

Most votes went to Germany’s hitherto second-largest party, the left of centre Social Democratic Party (SPD). Its candidate for chancellor, Olaf Scholz, was Germany’s finance minister during the pandemic under the grand coalition with Merkel’s CDU. As well as representing continuity from the Merkel era, he also carried a bit of the ‘Rishi Sunak’ bonus, having been the politician seen to minimise financial hardship during the pandemic.

Furthermore, many young voters opted for the Green Party and the liberal-but-business-oriented Free Democratic Party (FDP), rather than for the more extreme outliers on the populist right and left (AfD and Die Linke). This makes a coalition between the SPD, Greens and FDP the most likely outcome of forthcoming coalition negotiations. If it indeed ends up that way, markets may be quite happy to see two forces for fiscally-driven change (SPD and Greens) being held in check by a party opposed to too much state intervention and tax rises. This sounds to us like an emerging change agenda the German way, which you can read more about in the next article.

Politics are also our closing point this week, with the US debt ceiling crisis temporarily averted -as we suggested in last week’s article. As the crisis has not been resolved, markets have not (yet) rebounded in relief, but it is fair to say the downdraft in risk assets abated towards the end of the week.

As we said last week, such post-recovery periods that follow recession are often characterised colloquially as ‘climbing the wall of worry’. But we take heart from this week’s seeming shift in sentiment towards the cyclical recovery theme, even if the winter months may prove somewhat nerve-racking while supply chains are straightened out after the turbulences of the extraordinary efforts of keeping things ‘on the road’ during the pandemic.