Rollercoaster for the Jubilee funfair

Posted 1 June 2022

Party stalls are going up and libations are flowing for the Platinum Jubilee. But no fairground is complete without some thrilling rides. Over the last month, capital markets chipped in with a rollercoaster of their own: equity indices jumped in the first few days of May, only to sink frighteningly low mid-month. At times it felt like markets were in meltdown, with investors buffeted by fierce global economic headwinds.

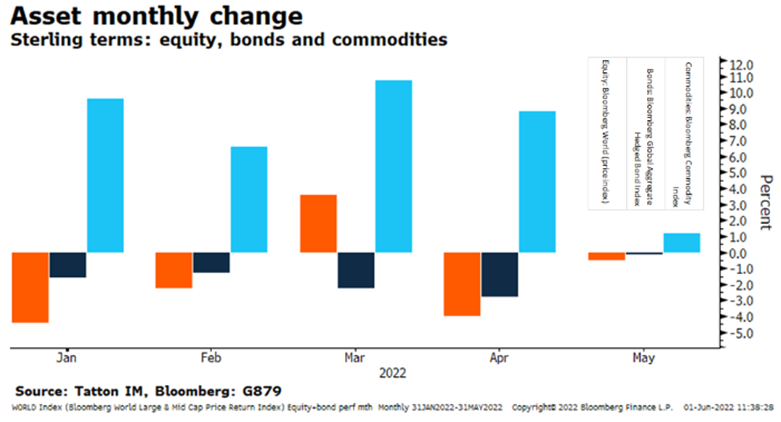

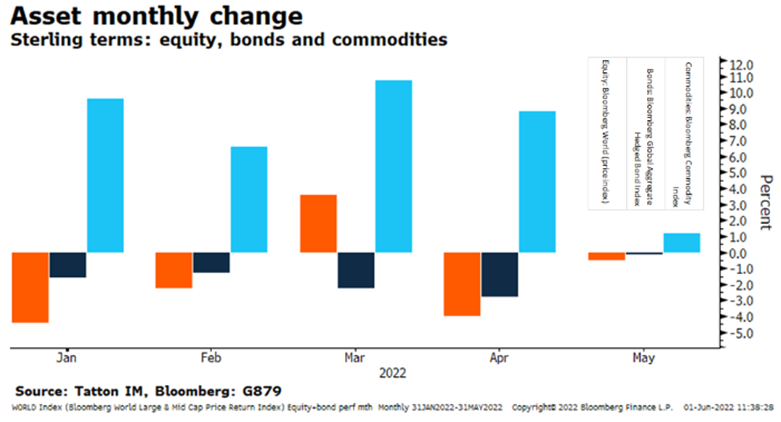

The thing about rollercoasters, though, is that they eventually end up right where they began. A late rally eventually saw global equity prices climb back up to where they started. Bond returns were virtually flat as well and even commodity prices could only gain a net 1% in May. In the end, markets recorded their lowest monthly change this year. As you were then; keep calm and carry on.

The fears that set off this wild ride were threefold. Central banks are tightening policy around the globe and sapping liquidity from the financial system, rapid inflation has bitten a chunk out of people’s disposable incomes, and another round of lockdowns in China has plunged the world’s second-largest economy into a sharp downturn. Too strong a combined headwind for post Covid demob happy consumer spending to neutralise.

There is some debate about which of these factors has the most impact. Consumer demand has fallen on the back of sharply higher prices – but labour markets are still tight, providing plenty of income-earning opportunity, and US retailers revealed decent profits just last week. Central banks are unequivocally in tightening mode – but there is still ample liquidity and interest rates are low by historical standards. COVID restrictions have weakened the Chinese economy – but production has held up better than other components, and this acts as a counterbalance to global inflation.

What no one can dispute, though, is the end result. Growth indicators have significantly slowed in the western world, and in China they have all but collapsed. In the earlier part of May, the recession questions being asked were ‘when, and how bad’ rather than ‘if’. In the UK, this was apparent from the Bank of England’s (BoE) latest growth forecasts, which predicted inflation of more than 10% by the end of the year, and a shrinking economy in 2023.

A month is a long time, though, and by the end of May things looked distinctly less gloomy. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) has been itching to tighten financial conditions all year, but the very fact that markets have slumped seems to have done a lot of that work already. Having raised rates once, it looks like the Fed has found the economy’s ‘biting point’ already. So, judging by the latest market reaction, it may not have to step on the brakes any harder.

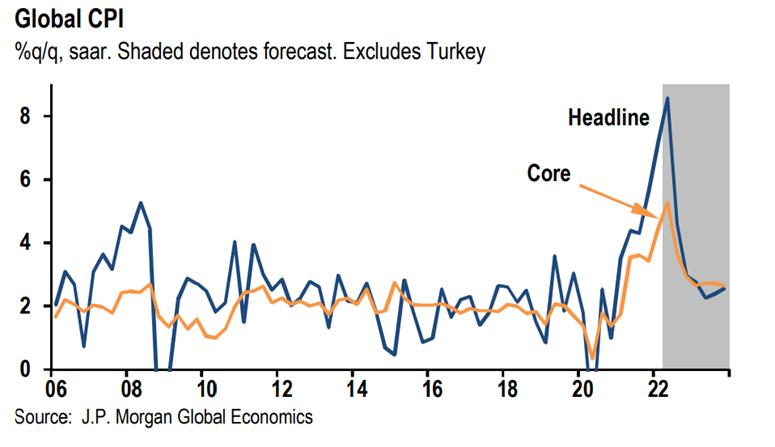

Markets now believe we are past the peak in global inflation pressures (though the year-on-year rate of change may not peak for a few months). US mortgage applications are falling while lumber prices (a sign of housebuilding activity) are declining. The Fed will take this as clear signals that the economy is cooling down – and may well judge that its policy has worked.

As mentioned, the weakness in China has helped cool global inflation. COVID outbreaks and the government’s zero-COVID policy have forced lockdowns across the world’s most populous nation, dramatically reducing consumer demand. This gives temporary respite as we battle with sharply higher prices, but ultimately the world economy will suffer if China continues to flag.

Fortunately, extreme lockdown measures appear to be easing. Even better, the Chinese government has signalled that future outbreaks will not be dealt with as harshly. Last week, Premier Li Keqiang told officials they must balance virus containment against the nation’s economic growth. This is a positive for China over the medium-term, and so too for global growth. Chinese equity markets have started climbing from their lows, and the Renminbi has gained against the US dollar. A sense that China will be stable once more now pervades markets.

Elsewhere, oil and gas supply remains a major concern. Last week, the European Union (EU) announced an embargo on Russian oil, pushing prices higher again to nearly $124 per barrel. But this is expected to be more of a restructuring of global energy flows than a dismantling, and so the sense of dislocation is no longer as strong.

The 15 member countries that make up OPEC+ will meet on Thursday, and Russia’s production ‘quota’ is expected to be removed. Russia’s amount will likely be allocated elsewhere though, allowing those nations with more flexible capacity to pump out more crude – which could easily reverse the supply reduction that global oil markets have suffered because of sanctions placed on Russia. In particular, Saudi Arabia is expected to step in. On that front, frosty US-Saudi relations seem to be thawing, with President Biden rumoured to be heading to the Kingdom for talks. This would have been impossible in the immediate aftermath of the murder of Saudi dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi in 2018, and highlights how Russia’s war has warped geopolitical priorities around the world.

With an improved outlook for China, and a possible peak in energy prices, the global economy looks to be on a firmer footing. The recession fears that swept up investors a few weeks ago have subsided, and markets now appear to only expect a slowdown – rather than a full-blown contraction – in the short to medium-term. That is important, since recession takes a major toll on credit markets and equity earnings, which can be hard to recover from in the short term.

We should not get ahead of ourselves, though. Global input inflation may have passed its peak, but there is still plenty of feed-through and second round effects to come. For Britons, this is clearest in household energy bills, which are expected to jump once again in October, and could cause serious pain for many of the worse off.

Even with fewer problems in the supply of goods, labour markets are still tight across the developed world, and the gap between jobs and workers will not drop away anytime soon. Consumers are still spending and borrowing, as credit card data suggests. Savings ratios – which built dramatically through lockdowns – have plummeted pretty much everywhere, and are only slowly building back up.

Central banks are still intent on preventing a wage-price spiral – and that tightening bias will continue to be a headwind for equity valuations. As we enter June, fears of short-term catastrophe have subsided. But this is far from the all-clear, and we are still waiting to see what the post-COVID ‘normal’ really looks like.

In the spirit of the Jubilee, we would do well to remind ourselves of thinking for the long-term. As our cartoon of choice this week shows, Queen Elizabeth II’s 70 years on the throne have seen more governments – and prime ministers – than one could wave a stick at. Many of them no doubt caused a lot of noise during their respective terms in office. Like the Queen might be inclined to do, we prefer to look over the long-term – and chart the best path to future growth and prosperity.