Special market update: Russian intimidation of Ukraine

Posted 16 February 2022

From our phone calls and conversations we have with adviser firms, we know portfolio investors are concerned that the fear of Russia invading Ukraine is driving, at least in part, the poor start to the year experienced by capital markets.

As laid out in recent editions of The Tatton Weekly, the cause of the current market volatility is not being caused by fears of Russia’s President Putin starting a European war, but is rooted in concerns that central banks may be moving too rapidly from monetary easing to tightening. Nevertheless, the two are loosely connected. Putin’s actions have left energy prices elevated for longer, which in turn keeps consumer price inflation elevated, which has arguably increased the pressure on central banks to act.

The current situation is undoubtedly worrying, and the political tensions are only exacerbating the most recent market weakness. Therefore, as we always do at a time of market-moving activity, we wanted to share our thoughts in a supplemental investment update. So, let’s begin by looking at what investors can learn from previous episodes of geopolitical stress.

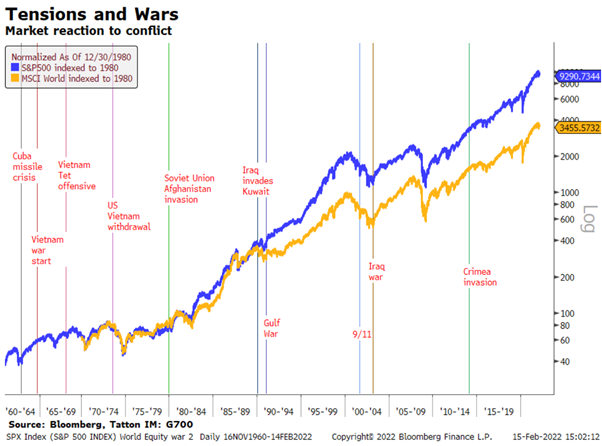

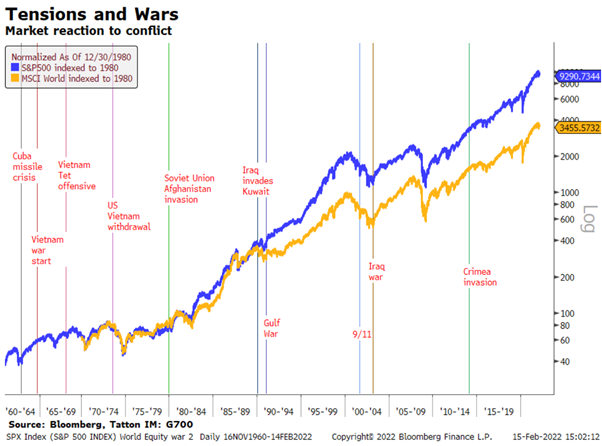

Recent history has relatively few episodes of war and near-war that might be considered to have been of global significance. Surprise actions such as the Iraq invasion of Kuwait and 9/11 (in 1990 and 2001, respectively) had negative impacts only after the event. However, drawn-out episodes have seen market weakness in the lead-up to but not after the outbreak of conflict. Both US-Iraq wars marked the start of stock market rallies, as did the Cuban Missile Crisis.

On those occasions, there were several other factors – aside from geopolitical tensions – which had contributed to weakness beforehand. Moreover, we also cannot attribute market strength to a sense of resolution. Nonetheless, it demonstrates that markets are reasonably efficient around such events; they go through a gradual process of discounting risk ahead of the event, rather than having a sudden unexpected dislocation as war starts. Unless they seriously impact global growth, we should expect the impacts caused by the negative surprise to pass quite quickly. Using this fairly limited history as a guide, from the current position, there is potential market upside as well as a downside.

In other words, we think the past tells us that – on balance and in market terms – we should not be too worried about market returns if the worst happens. Nonetheless, it is important to try to assess whether the current situation is markedly different.

At this point, various markets have already priced in quite high levels of risk and consequence. This is particularly true of energy. Natural gas prices have been squeezed much higher this winter. Speculative buying has been a factor, but Russia’s actions in suppressing supply have almost certainly been the biggest driver. As we have noted before, Europe’s weak spot is its reliance on Russian energy, especially natural gas. The chart below shows that the gas supplies have been cut repeatedly, and do not seem to be related to the pandemic.

Russia still needs to sell its oil and gas and Europe remains its major customer. According to Russia’s central bank, total exports (not just energy) reached $489.8 billion in 2021. Of that, crude oil accounted for $110.2 billion, oil products for $68.7 billion, pipeline natural gas for $54.2 billion, while liquefied natural gas accounted for $7.6 billion (In sum 49% of all exports). While the rise in prices will be welcome in Moscow, it will gain little if Russia cannot sell the volumes needed.

Growth in Russia is forecast to slow down to 2.3% for this year, having reached 4.3% in 2021. These growth numbers may sound healthy enough but, given the rise in energy prices, they are in fact mediocre. The Russian Ruble would usually benefit substantially from rising energy prices but has already declined 5% since peaking against the US Dollar in October. Russian foreign currency debt credit spreads have widened, and local interest rates have risen sharply. Russia’s financing costs face an even worse outcome if war breaks out. Russia’s citizens are unhappy, and the prospect of a war that threatens to kill or injure many young Russians is likely to make them even less so. Given this economic backdrop, we suspect Putin’s posturing will remain just that. Should there be an actual armed conflict, Russia needs it to be as short-lived and containable as possible.

Events can change dramatically from one day to the next, however, we believe that current markets have already priced in the risk of a worsening of the Ukraine conflict within the confines described above.

As we mentioned at the beginning, markets face a more substantial threat from policy tightening by central banks and governments. It may seem odd but if the Ukraine tension drags on or worsens, policymakers will feel less obliged to depress economic sentiment further.