Spring of hope following winter of doom?

Posted 6 April 2023

This year began in anticipation of imminent global recession, but imminent did mean immediate, and as the second quarter gets under way, the chances of a global recession may be less now than they were.

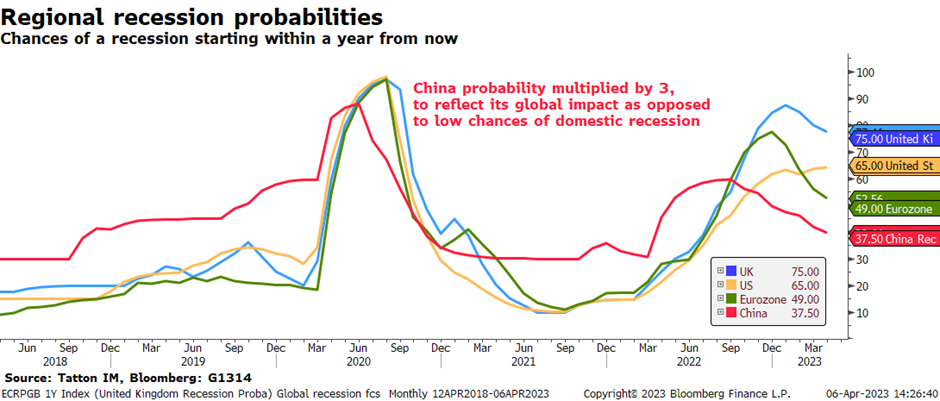

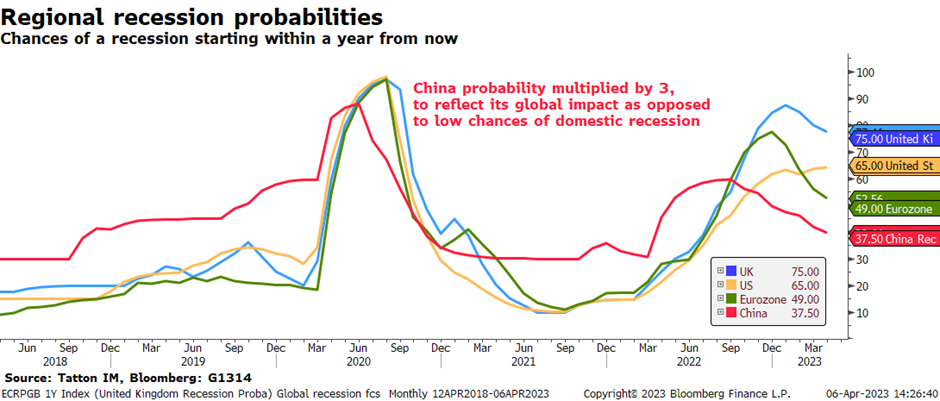

The chart below is Bloomberg’s calculations of the chance of recession occurring within a year, for each region. As it hopefully shows, a combination of events in the first three months has reduced the likelihood of negative real growth occurring in the next 12 months in most regions.

The exception is the US, where chances have increased marginally. The most interesting outcome of this is that it may have reduced the chances of global recession even more.

The calculations are made as of the end the month (we also smooth the data to show a clearer trend). March saw a flare-up of bank mistrust, which gave investors and capital markets an uncomfortable reminder of the 15th anniversary of the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Bank lending was already tightening and events in March will have made it worse.

But rather than tipping things over the edge, markets have seen this as helping central banks in fighting inflation. Most price indicators still suggest a steady decline in goods prices. Against this, Europe and UK inflation was a bit sticky in March, and last year’s price shock may still be feeding through to the service sector, which makes it even harder for central bankers to decide how to proceed and harder still for strategists to forecast.

However, if demand is slowing in the US, global inflation pressures will continue to reduce. In turn, this means not just that a peak in rates is in sight, but also a sharp reduction in future rate expectations. The two-year US Treasury yield peaked on 8 March at 5.07%. Two weeks later, it was at 3.56%. Such a fall in yields (over 1.5%) has not been seen since Black Monday in 1987.

Lower government bond yields lead to higher equity price-to-earnings valuations, if all other factors are equal. However, a slowing economy is generally not good news on corporate earnings front. The data from the US for the end of 2022 showed a sharp contraction in economy-wide corporate profits, with smaller enterprises under real pressure. The danger for the larger companies that comprise most of our investment universe is that they too could experience a worsening earnings environment.

This week’s crop of economic data has added to the evidence that higher rates in the US are indeed creating a more difficult environment than elsewhere. Industry has already been slowing, but rates are more keyed on services, which had been expending smartly. This week’s Institute for Supply Management (ISM) data showed an unexpected fall, still at a mildly expansionary level of 51.2 but below the ‘inflationary’ level of 52.

Asia and Europe are showing stronger signs of economic spring thawing. China’s data is indicating a slow but steadily improving rise from the depths of Covid restrictions, as we felt would be the case.

The dollar has taken a hit this week, which may not be surprising given the economic backdrop. This has a general stabilising effect on the rest of the world’s economy and also helps to reduce inflationary pressures, and will also be a welcome impact for central banks, especially the European Central Bank (ECB).

Of course, this does not mean all is right with the world. After almost a decade-and-a-half of ‘money for free’ ultra-low cost of finance, there has been plenty of time and ample opportunity for misallocation of capital. As the Sage of Omaha (Warren Buffet) keeps reminding us: It is only when the tide goes out that we find out who has been swimming naked.

It may be that the weaker data from March was directly caused by the fears about banks. Those fears have passed quickly and nobody other than the banks’ equity (and Additional Tier 1) holders have suffered – a very small group. As such, the forthcoming data could bounce back and, with it, inflation. In that case, we’ll be back to square one, only with a weaker set of small businesses.

Investors may read from the pedestrian positive returns of their portfolios over Q1 (if they are invested in globally diversified multi-asset portfolios) that capital markets and their prospects have continued on a gradual path of improvement since Q4 2022. Herein lies the fragility and difficulty for the coming quarter: Will a less bad economy and receding valuation pressures continue to provide support for stock and bond markets?

Will the lack of earnings mean unsustainable losses, further ‘falling dominoes’ or unrelenting central rate hikes lead to another market capitulation as witnessed last October? Right now, the risks feel finely balanced. Can inflation continue to decline, or will it take another financial sector blow-up to make central banks more dovish?

At this point, we are happy enough to have stocked up on long maturity bonds in portfolios when yields spiked higher, but otherwise remain neutral on risk as the second quarter of 2023 takes its course.