Trust the MPC to rain on May’s parade

Posted 12 May 2023

After a period where it felt like there was a shortage of news, things are hotting up. Both equity and bond markets are bearing up well generally but, in our estimation, underlying risks have increased since May started.

After last week’s rate rises in the US and Europe, this week it was the turn of the Bank of England (BoE) to increase the UK base rate to 4.5%. While members of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) will have seen weak real growth data for first quarter of 2023 (+0.1% versus the previous quarter, with March slowing sharply by -0.3% versus February), BoE researchers raised their estimate for economic activity this year and no longer think there will be a recession. More importantly, they expect year-on-year inflation to take more time to slow, to remain above 8% as of June, and to finish 2023 at 5.1%. They say the risks are skewed towards inflation continuing to be high rather than below the BoE’s 2% target.

Not everyone agrees with them. The independent MPC members, Silvana Tenreyro and Swati Dhingra, wanted no rate hike. Meanwhile Michael Saunders of Oxford Economics – a former independent MPC member , and a noted hawk in his time there – believes UK inflation is set on a downward trajectory. He thinks risks are skewed towards an undershoot of the target, and that this rate hike will probably be the last in this cycle.

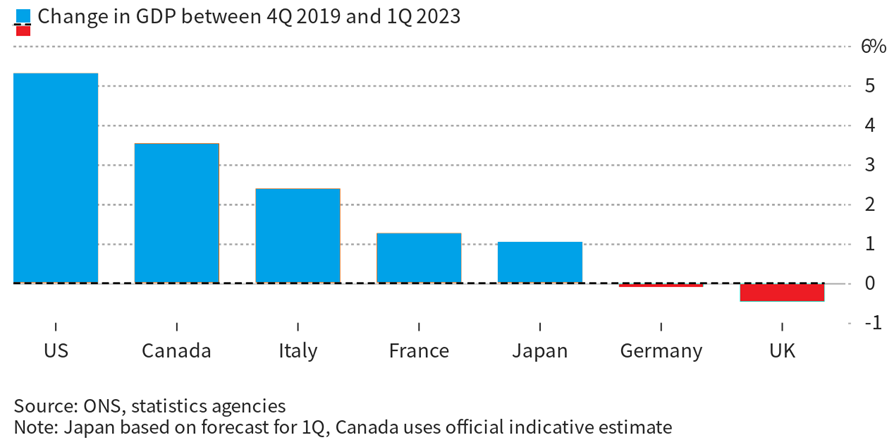

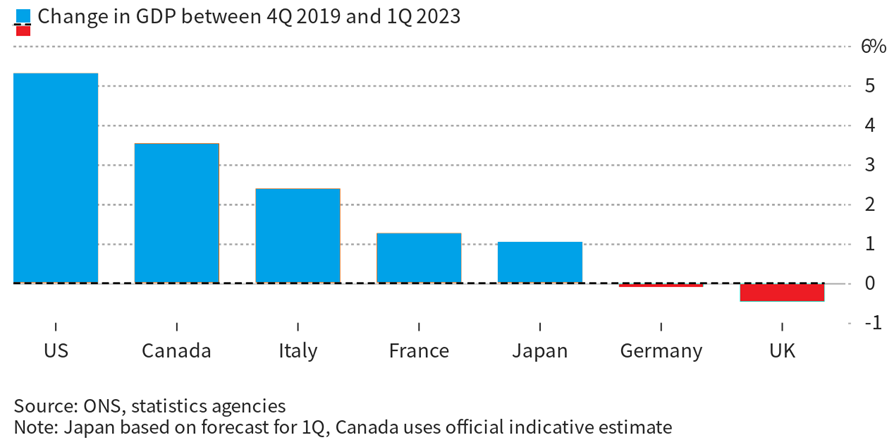

The past three years have been tough for the UK. Below is a Bloomberg chart showing the total change in real gross domestic product (GDP) for European nations and Northern America;

The fact is that over the past few years, the UK has faced production capacity issues which other countries have not. For various reasons, we have not had enough resources to fuel overall growth. The biggest resource shortage has been the skilled and unskilled people needed to do the work. The BoE still worries this is the case, which is why it sees inflation risks skewed to the upside and it’s difficult to see how this will be resolved in the short to medium term.

The problem, for all of us here, is how do we get to a situation where UK businesses can be globally competitive if workers of all stripes are not readily available? If labour gets paid more, the impact on businesses is to be less globally competitive, so there will be a steady outflow of jobs. Whole economy real growth will remain consequentially low. The data seems to tell us this may have been occurring, and the imbalance still exists.

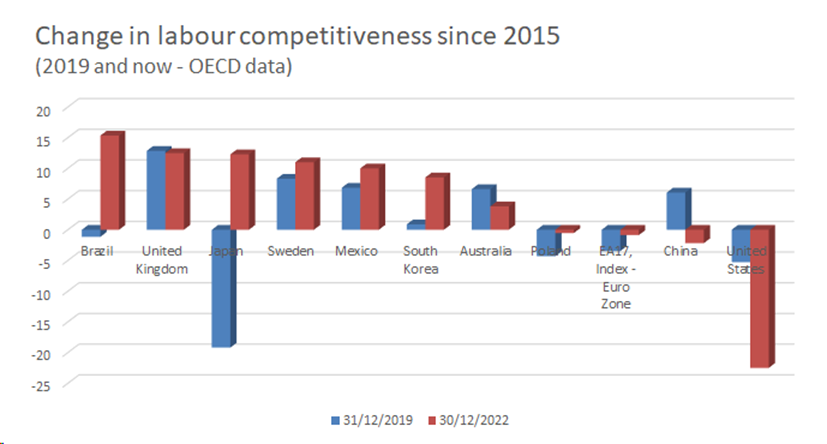

There is reasonable evidence that UK wages have fallen. According to the OECD, we have gained labour competitiveness on a relative basis since 2015, although that hasn’t change over the post-pandemic period. Below is a chart showing different countries and regions (Tatton IM adjustments from OECD data):

But there is a problem. That change in competitiveness means workers are paid less comparatively. The Japanese may feel poorer but, for their economy, it’s a relatively good thing since those workers stay in Japan. Whereas in the UK, workers shift to better-paid areas. This is particularly so for highly-skilled workers such as doctors. It doesn’t solve the issue of lack of resources. Over the long term, training our youngsters well (and retraining our not-so-youngsters) will have the biggest impact. Before then, a dose of realism about retaining and attracting skilled workers is important – that’s not just about pay but about creating nice places to live.

Meanwhile, the environment for businesses in the developed world remains difficult. The rises in short-term rates has happened almost everywhere and at the same time. Indeed, apart from the early 1980s, there has never been a such a period with virtually all central banks acting as if in concert. That unified action also means their policies have an unprecedented global impact, magnified by a more interlinked world than in the 1980s. At Tatton, we’re sure that central bankers take into account the impact of each other’s decisions and yet this final phase of rate rises could be viewed as coordinated overkill.

Money supply has been contracting in the western countries since the start of the year, and house prices have been falling in almost every region except Japan. Producer prices are heading into contractionary territory. Energy prices particularly are falling. And, in the US, the labour market indicators tell us the jobs market has moved to a weak rather than strong dynamic.

The US is always at the centre of global markets, so the possibility of the US government defaulting on its debt commands much attention. We write about some specifics below, but there is a wider aspect which we will touch on here. The strength of the western world has depended on the strength of its institutions, which are reliant on the ability to compromise. Recent years have seen the rise of division and that could be dangerous if carried too far. It will be important for the US and for the rest of the world that this situation does not occur. Despite both sides stating they have no latitude, President Biden has already indicated some leeway. In 2011, Obama gave ground and a default did not occur, although equity markets had a rough ride. We are just over two weeks away from the first possible point of default. Let’s hope for considered realism on both sides of the party divide.