Winners and losers

Posted 27 August 2021

Fed tapering: the ‘how’ matters more than ‘when’

Questions over when and how the US Federal Reserve (Fed) would begin tapering its monthly securities purchases has been much talked about over the last few months. But ahead of today’s keynote speech at the Jackson Hole symposium, questions have been shifting increasingly towards ‘how’ the Fed tapers, instead of ‘when’. Today we got an answer, of sorts. Fed Chair Jerome Powell confirmed the Fed could begin reducing monthly bond purchases sometime this year, given the US economy has met the self-imposed test of “substantial further progress” towards its inflation objective, and after “clear progress” from the US labour market. Powell also suggested the Fed would like to conclude its bond buying programme before raising interest rates, underlining the lack of a mechanical connection between tapering asset purchases and starting with rate hikes.

It may be surprising that a central bank could scale back security purchases just as the economic momentum weakens, fiscal stimulus wanes, and societies at large are still in the process of finding a way to live with the virus as it becomes endemic. At the same, finding a way back to normality also inevitably means waving goodbye to extraordinary policy support measures. As a reminder, currently the Fed purchases to the tune of USD 120 billion per month (USD 80 billion of US Treasuries and 40 billion in Mortgage-Backed Securities.

Something which should buffer the immediate liquidity hit to markets is that the Fed ‘overproduces’ liquidity. Money markets cannot absorb the Fed’s purchases unless interest rates fall to zero or below (we wrote about this in a previous weekly). Currently the Fed drains via reverse repo operations (to the tune of USD 1.4 trillion). Should the Fed begin to purchase less, some liquidity can easily be released back into the market.

Of course, beyond almost mechanical liquidity effects, markets trade on signals and policy expectations. Given present economic uncertainties, it is vital the Fed maintains confidence in the economic recovery. In this sense, a short and sharp taper could be counterproductive, hence the wording from Powell around “carefully assessing incoming data and the evolving risks”. Tapering to a conclusion by the end of Q122 (as suggested by James Bullard) appears too harsh, and the more market-friendly approach is to present a pragmatic policy stance that remains flexible enough to make any necessary adjustments, should the outlook deteriorate from where we are now.

The Fed will never tell you, but not only ahead of today’s keynote speech from Chair Jerome Powell but also further out, the Fed should keep a close eye on the shape of the US Treasury curve. Given the current stage of economic recovery (this is not yet a mature recovery phase), a further flattening is undesirable. The 2-10-year spread (difference in the yield) has already tightened over the last couple of months, as Fed members have talked about bringing forward their expectations for higher policy rates. Now, it has to decouple tapering from rate expectations – currently money markets expect a lift-off for rates in Q1 2023, and nothing from Powell today contradicted this view.

In the following article we explain why the US equity market could stomach slightly higher real rates in response to fewer Fed purchases. Further out, financial markets will increasingly react to the earnings outlook, as the pure policy impetus begins wane. The global economy is also currently still in a transition phase, and whether a self-sustained recovery can be engineered remains open to question. In this case, it may not only be the expensive cash-rich companies that thrive, but also those trading at lower multiples currently.

Another area that occupied people’s minds this week has been the intertwining outlook for the US and the rest of the world. The first guidepost for any central bank is domestic conditions, and for the Fed, namely the labour market. But over the past few years, the Fed has opened-up to global developments and vice versa. For example, the European Central Bank has already made it clear it would react should Fed policy action create negative spillovers into the Eurozone.

The most obvious translation of Fed policy into the rest of the world is the US Dollar. Should it appreciates too much, this not only tightens financial conditions in the US, but also in Emerging Markets (EM), which again underlines the need for a measured exit from quantitative easing. But for now, the risk of a rising USD persists. This may also explain why ‘cheap’ EM equities have not attracted broad-based buying from global investors.

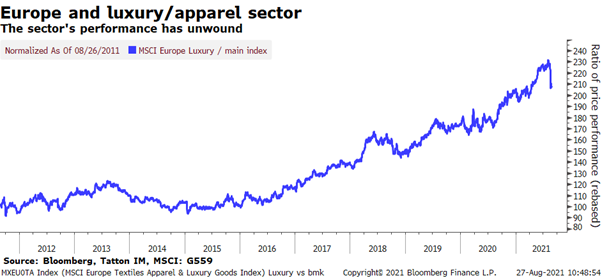

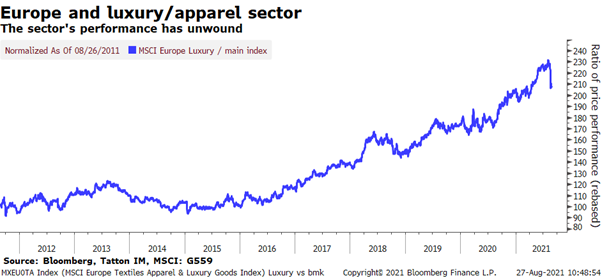

And of course, China’s regulatory drive has been another defining element. As China’s property conglomerate Evergrande appears to edge closer to a resolution process (which sometimes can signal a bottom), other areas stay very much ‘live’ in China. Following the crackdown on finance and big tech names recently, it has been the turn of luxury goods to react to China’s drive towards equality. The fear is that a crackdown on the wealthy may signal lower sales and margin figures, which saw European luxury brands sell-off sharply. Our final article this week explores the singularly Chinese concept of “common prosperity”, which is guiding regulatory action across a multitude of sectors. While any transition phase is painful, it is worth keeping in mind that a broad-based rise in living standards could also signal greater volumes – even if the style of luxury products may have to adjust.