Europe remains in focus

Posted 22 July 2022

Global investors tend to be quite US-focused, as the world’s largest economy has an outsized impact on trends across the world. This week though, attention was on the other side of the Atlantic. European economic data caught the eyes of traders – and unfortunately not for the right reasons. Both consumer and business sentiment surveys indicated unexpected weakness, heralding a downturn across the continent.

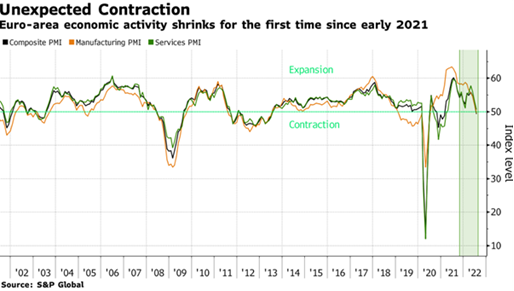

The chart below shows the path of Purchasing Manager Indices (PMIs). They record business confidence (out of 100) across a range of categories. Readings above 50 tend to indicate that economic expansion lies ahead, while figures below that level point towards a contraction. The PMI’s this week were not good for Europe. Each index was one or two points below the expected level, and the composite index (combining services and manufacturing) fell to 49.4. This would seem to signal that Europe is on the brink of a recession, if not already in the midst of one.

At the start of the year, there was a great deal of optimism about Europe’s post-covid economy. It is hard to find such positive sentiment now. An ailing economy and perennial political divisions have been exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Given its reliance on Russian energy, the European Union is particularly susceptible to the war taking place on its borders and its energy insecurity has led to sharply higher inflation expectations.

Europe is not the only place where optimism has faded. In the US, the corporate earnings season is underway and has disappointed. There is no disaster apparent in the figures, but earnings expectations have taken a clear downturn – particularly for next year. American earnings are still expected to rise, but the path is flatlining. This is part of a global theme: growth and earnings are under pressure, with little signal that these will improve.

With all this doom and gloom, one might be surprised to learn that this week was a good one for equity markets. Despite lacklustre US earnings, the S&P 500 gained more than 4% on Monday’s level. Even more surprising is the Euro Stoxx 50, which is more than 3% up this week at the time of writing. Both indices are well above where they started at the beginning of July. Economies have weakened but markets have rallied. How do we make sense of this conundrum?

The key factor here is not the weak economic data itself, but the policy response to it (or rather, the expected policy response). We cover the European Central Bank’s (ECB) recent actions in a separate article this week, but the truncated version is as follows: the ECB measures are far from perfect, but there is a concerted effort to do something about energy price inflation and the knock-on effects on the wider economy. This is important, as strong and responsive institutions are essential for Europe’s crisis response.

As for the US Federal Reserve, we can be fairly certain that policymakers will raise interest rates by another 0.75% at their meeting next week. There is a small chance the Fed could go even further, in an attempt to reach its ‘peak’ interest rate sooner. Again, we cover central bank expectations in a separate article on bond markets. But we note that discussion around peak rates – what and when they will be, and policy will evolve after that point – has proved a positive for capital markets.

Interestingly, recent policy announcements have shown a potential advantage for the ECB over the Fed. Monetary tightening tends to be a blunt instrument – hitting everything at once but damaging some parts more than others. But the ECB’s new Transmission Protection Instrument will allow it to buy the bonds of weaker Euro nations, so that they maintain funding through this difficult period. This allows the central bank to raise rates more aggressively while offsetting the impact for the worse off. There is even some suggestion that the bank might buy corporate credit for the same reason – though the details are not known.

This has made it a good week for risk markets. With central bank help (particularly from the ECB) credit spreads – the difference between government and corporate bond yields – have fallen back sharply. This is despite weaker than expected economic data and aggressive monetary tightening. In our model for valuing risk assets, credit spreads are just as important as bond yields themselves. As such, falling credit spreads have helped prop up valuations, even though other factors (like earnings) have deteriorated.

Of course, investors do not make all their decisions via complex valuation models. A more psychological or narrative-based explanation for why equity markets have improved is that investors feel they are being given permission to do so. Earlier this year, it looked increasingly like the Fed would have to engineer stock market weakness in order to prevent the economy from overheating. That is, there was a sense that policymakers needed to depress asset prices to tame inflation. That narrative has now changed.

Sub-par growth in the economy has now taken a firm hold it seems, partly though monetary tightening and partly through a global cost-of-living crisis which is destroying demand. Investors suspect that Central bankers can see the point being reached at which they no longer feel they have to suppress markets. They may be worried about the effects on companies (as we can see through their attempts to shore up credit spreads). Essentially, investors feel they no longer are the only ones to pay the price of slowing the economy.

This is a boost for markets. Central banks have instilled confidence over financial stability. In spite of the current inflation crisis, fears of widespread defaults have receded, and there is a sense that the fallout in capital markets will be limited. Talk of ‘peak’ rates and what will happen after them adds to this: things may be difficult now, but it may well soon be over, and investors stand to gain when it is.

There’s a lot of debate about UK tax policy at the moment. We certainly have no intention to take sides on political matters. It is interesting to see the final Conservative Party candidates vying for the position of Prime Minister seeking to take such polarised positions in such a debate. Of course, in a two-party system, the main parties are always coalitions of factions but one wonders where this open disagreement will leave the present Government following this fractious and protracted pubic confrontation.

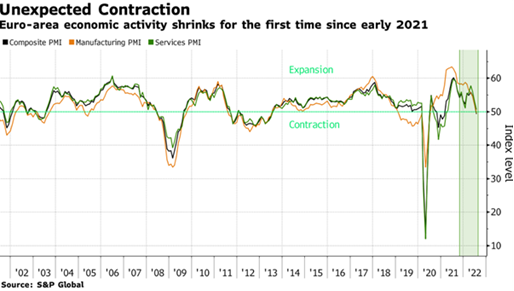

In recent months, UK government finances have been doing better than the Office for Budget Responsibility had expected. However, what inflation gives (in terms of rising taxable bases such as VAT and rising earnings), it takes away with the other. Interest rates are going up and unless inflation is brought under control, it could overwhelm the public finances. The data released on the 18th July showed how interest costs have risen sharply as part of our debt is funded through inflation-linked bonds. Of course, we also have to refinance maturing fixed debt. This data from the Institute for Fiscal Studies gives cause for concern.

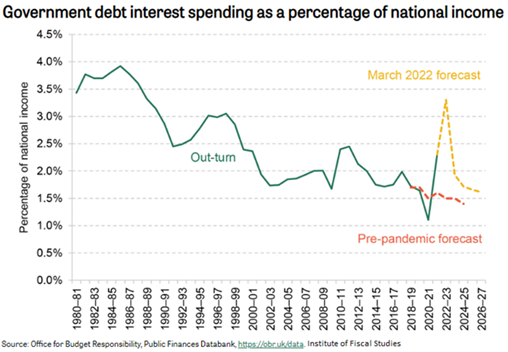

Debt expanded hugely during the pandemic period as the chart below shows (which excludes the debt issued to pay for the banks bought in the financial crisis):

So now a smallish rise in interest costs has an outsize impact upon government finances, One can see why Rishi Sunak wants to argue for the public finances to be stabilised before committing to reducing the overall tax burden. It is also not surprising that it will be difficult to pay down some of the debt without having higher taxes. A near-term tax giveaway would have to be followed by a return to higher taxes or a substantial reduction in public spending, including a reduction in public investment. In such circumstances it would seem the Levelling up agenda could well be in peril.

Economists such as Dr Gerard Lyons make the good point that setting the country on the path to sustained growth is the way to pay down debt. However, it is not clear that the private sector has the capacity to provide the investment engine needed (monetarism has been closely associated with hard-line distrust of public spending). Meanwhile Liz Truss’s supporters argue that we find ourselves currently in a war-like situation which justifies higher public debt levels. Of course, a good proportion of the growth in the 1950s and 1960s came from government-investment, and that is very precisely not what is being proposed now.

While equities may perform neutrally or even better if Liz Truss were to win the race to be UK Prime Minister, sterling and bonds would probably struggle initially.