The flipside of inflation – growth

Posted 15 March 2024

Consolidation continued in most equity markets this week, although bond prices did actually drop somewhat. UK and European equity markets are stronger, Japan is weaker and US large caps are largely unchanged, although there is a sense of mild disappointment as investors wonder whether US large cap optimism has got ahead of itself. At the same time, their optimism about earnings growth remains strong. So should equity investors worry that the ‘locomotive’ US market is finally slowing, while Europe and the UK markets are perking up even though their economic growth reports look dire?

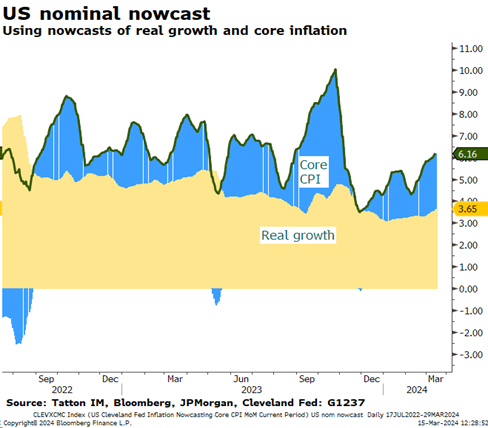

Corporate earnings which underpin stock market growth have been on a sharp rise in the US since the beginning of the year, supporting rallying valuations there. Indeed, earnings estimates are rising at around a 10% annualised pace for the past month according to our calculations from Bloomberg data. This has tracked a pick-up in nominal growth activity, again according to Bloomberg “nowcast” indices.

The nowcast measures use various economic data sets to calculate the current rate of real growth and core CPI inflation. The chart shows how total nominal activity (adding together the real growth in yellow and inflation estimates in blue) is evolving.

What may be seen as the proverbial fly in the ointment is that US inflation data for February, as released this week, was stronger than expected, as it had already been for January.

The US Central Bank decision making body, the Federal Reserve Open Markets Committee (FOMC), which meets on Wednesday next week, will probably be discomforted with a rate of nominal expansion higher than they were expecting. This feels somewhat similar to last summer. At that point, investors collectively believed that inflation was likely to continue to abate and a policy pivot was close at hand with rates quite likely already having peaked. In fact, it turns out that the view was right and the July 2023 was the last rate rise by the Fed (at least so far).

However, as the chart shows, the dip in inflation was then followed by a nasty acceleration. The FOMC, which had warned that their policy was still biased towards further tightening became very vocal. Their mantra was ‘higher for longer’ and the rhetoric was a major factor in the 10-year treasury bond yields shooting up to over 5% and the S&P 500 falling from August to October by 10.5%.

From our point of view, this current rise in inflation is not greatly troubling in the medium-term. Both households and businesses appear to be rate-sensitive and even moves of less than 0.5% in bond yields already slow activity markedly. To that extent, the FOMC can signal some hawkishness and expect the bond market to once again do the tightening for them. The economy is not running as hot as it was last year, and a rise in yields above 4.5% would probably be enough to slow things again. Equities might face some pressure but less than last autumn.

Indeed, following the autumn wobbles, the Federal Reserve should be congratulated, that despite its slow reactions, it has enabled employment to remain robust while inflation has been declining, because historically that is not usually how it goes. Consistently strong employment is the best ingredient in the economy’s pie as households are better and more immediate spenders than businesses. And spend they can, because the improvement in household balance sheets during the pandemic means wage earners can maintain more than adequate savings levels and continue spending as their disposable income increases.

The FOMC will still be pleased that labour has been very productive, and not just more expensive, and that might allow them to be more sanguine about the incoming data. They will also see some signs that consumer-wage earners are marginally less certain about further wage gains and may be tempering consumption, as indicated by February’s retail sales data. Despite solid household balance sheets, spending has been soggy for each of the past three months.

The flip-side is that the FOMC has little room for complacency when the economy appears to approaching capacity. The resumption of monetary growth that is beyond their direct control as it originates from increased commercial bank lending, leans toward a decision to hold rates. We would not expect a repeat of the market ructions of last autumn but should be prepared for a bit of short-term volatility next week.

Outside the US, one G7 central bank has already been giving out hints of a rate rise this week, while another has been sending signals of rate cuts.

The Bank of Japan, also meeting next week, has briefed journalists that an end to its “Zero Interest Rate Policy” is at hand. Unsurprisingly, the Japanese equity market took a sharp tumble on Monday as a consequence, while the Yen staged another bounce against the US dollar. Expectations of inflation have now filtered through to private households and wage rises are on the rise.

Indeed, Japan’s annual “Shunto” or business-union wage negotiation round was concluded on Wednesday and as the FT reported: “Economists expect large companies to give their unionised workers an average wage increase of more than 4%, compared with 3.6% last year. That would be the biggest rise since 1992.”

Yet, we should not expect a UK/US-like monetary tightening cycle. It is likely that interest rates in Japan could rise by 0.15% next week and possibly to 1% over the course of the next twelve months but it is unlikely to go further. The underlying strength of the turnaround in the Japanese economy is not going to be disturbed by these moves and it is possible that the positive impacts on confidence will outweigh any small tightening.

Europe’s central bank, the ECB, met earlier this month, but they met again this week to discuss their operational framework and the Governing Council members seem to be lining up behind a June interest rate cut. While some members are reluctant to move before any US easing, the majority appear to be convinced that manufacturing weakness outweighs a resilient labour market. The January industrial production data was horrible at -6.7% year-on-year. It is true that manufacturing sentiment has started to pick up, but that is in part due to the hope that rates will be cut. Meanwhile, the decline in production clearly signals excess capacity. The stable and low unemployment rate is seen more as employers ‘hoarding’ labour, which has resulted in workers being under-utilised.

The UK has a similar picture, but perhaps with a tighter labour market. The Bank of England also meets next week, and we can expect the Governor to tell us there will be no rate move and that they see everything as evenly balanced.

Bringing it all together, the global story underneath all of this is about spare capacity. The world beyond North America has quite a lot of spare capacity to produce goods. There are few unemployed workers, but productivity can increase without the need for new jobs. The US on the other hand is not quite in the same position. They have resilient domestic demand and, notwithstanding the occasional softish data like retail sales, it appears to be strengthening further. On balance, there is not much remaining capacity in the US to produce more.

This means that earnings growth outside of the US has been anaemic but has the prospect of accelerating. For the US, as mentioned, earnings growth expectations are already strong and probably are at the limit of growth if inflation isn’t to be reignited. After lagging behind the US markets, the rest of the world may have a happier time.