What the return of volatility tells us

Posted 12 April 2024

The week has seen quite large price movements in asset markets even though, overall, equities are relatively stable. The UK’s main market index, the FTSE 100, is higher and among the better index performers globally. It came very close to closing Friday above 8,000, but just missed out (our table at the end shows the level at 2:30pm). However, bond yields are higher here and especially in the US (which means bond prices have gone down), which usually drags down equities. What stood out this week is that the reverse is true in Europe: equities are lower but government bond prices are higher.

As we have written here recently, the first three months of this year saw declining volatility across asset classes, and this helped risk assets to rise in price. Why is it, then, that this week’s increased volatility did not hurt riskier assets more?

In the US, there still seems to be a “buy-the-dip” mindset among many equity investors. For us, this suggests that US investors still have relatively high levels of cash assets and like to deploy them when prices drop. However, it also suggests that the markets are getting riskier, with some evidence that the cash balances actually may not be that far from historical norms. Meanwhile, valuations are very high in some stocks, but the cheaper stocks are not that cheap. They are justified if economic growth is strong but the US Federal Reserve (Fed) may not be prepared to allow that pace of growth. It may be inducing too much inflation.

Quite sizeable swings in the main equity indices have occurred in the past two weeks, sparked by signals of stronger than expected nominal growth, which pushed expectations of rate cuts further out into the future. The decline seen late last week even happened before Friday’s strong employment report, but then strong investor flows came to the rescue in late Friday trading. This week, US inflation data was stronger than expected, with core CPI rising to 3.8% year-on-year rather than continuing its decline. This is yet more evidence for continued economic expansion, close to or perhaps even above capacity of their overall economy.

The US bond market has certainly taken note of the combination of strong growth and inflation. The yield on the US 10-year government bonds rose as high as 4.59%, for the first time since last November. While investors generally think that the Fed will cut rates sometime this year, the probability of a cut in June, as implied by market pricing, has fallen to just about 30%.

The rapid rise in US government bond yields to new cyclical highs during the late summer and early autumn of last year coincided with the last meaningful pullback in broad US equity markets. However, bond yields had been creeping up before, and equities did well. For markets, as long as the interest rates are not seen as holding back economic growth or even threatening recession, equities definitely remain a good choice. So, the current repeat of rising yields in tandem with generally rising equity valuations in US markets suggests that the overall rate of real economic growth is not considered at risk, despite what appear to be high interest rates.

Undoubtedly, not everybody is doing brilliantly. The US National Federation of Independent Business, a small business association, released its well-respected monthly sentiment survey for March this week. It showed some despondency about future profits and the worst outlook in 10 years. Small businesses’ inflation concerns were previously coming down, but respondents are worried about inflation again.

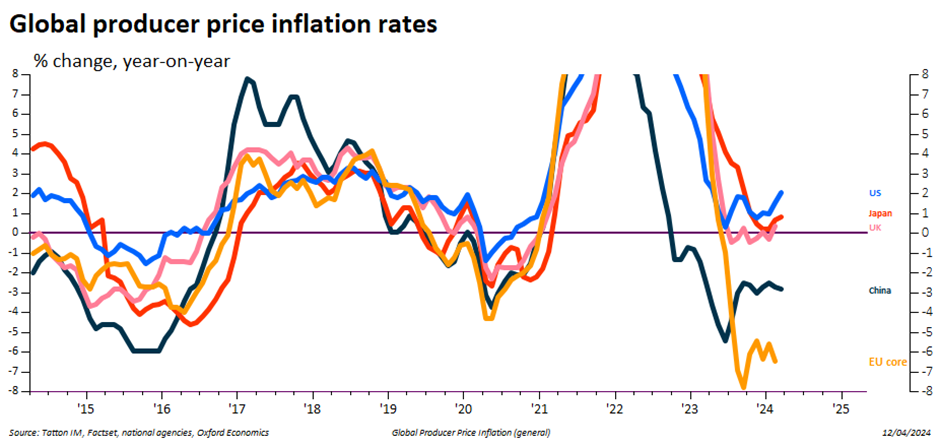

However, manufacturers are feeling better than last year and getting back to growth, according to the ISM Manufacturers Survey which came out last month. And we might infer from US producer price inflation that they are getting some pricing power back. March’s +2.1% year-on-year rate was actually slightly below economists’ expectations but the direction of travel is strength rather than weakness.

For US businesses (especially the larger ones) profits appear to be on the rise, thanks to reasonable revenue growth and an ability to maintain margins. Indeed, the combination of improvements means that analysts have been raising their estimates for “next-twelve-months” profits on the S&P 500 at a 10% annualised pace for much of this year. Historically, that’s achievable, but the 20-year average is about 6% and periods of better growth tend to occur only following a sizeable downswing in profits, which we have not had.

Bloomberg Intelligence tells us that the Mag-7 (the US tech behemoths) are “projected to rise nearly 38% y/y, while profits will decline about 2% for the rest of the S&P 500. The group will command superior growth throughout the year, analysts project”. That statement might suggest that future profit expectations outside the Mag-7 had been bad but “next-twelve-months” aggregate estimates have risen about 6% since May last year and picked up in line with the total index since the start of this year.

All-in-all, our observation is that mild growth optimism is fairly widespread and nominal growth itself is showing up in the economic data. Indeed, it is widespread enough to mean that few are under pressure. A few companies, like Nvidia, feel great.

Still, growth may get too hot for the Fed’s comfort. While this is not the roaring twenties, the economy’s momentum has started to pick up from already decent levels. Few (apart from Larry Summers) have said that they should raise rates, but neither the market nor the Fed may be able to stand another rise in CPI.

European company analysts do not share their US counterparts’ optimism, and neither does the European Central Bank (ECB) have the same problems as the Fed. While the US and Europe have similarly tight labour markets, the differences in the corporate sector are stark. Therefore, in their meeting held this week, the ECB made it clear that rates will start to be cut in June. They continue to look through the labour market’s potential inflationary drivers and focus on the pressures that companies are facing, especially in weak revenue growth. Returning to the reverse market dynamics of Europe versus the US, divergent economies were well reflected in the market reactions this week.

European analysts might be starting to raise earnings projections (which have risen about 6% annualised from projections a month ago) but this follows nearly six months of projections declining at a 4% annualised rate.

The producer price data (shown in the previous chart) is probably good evidence for this. Manufacturing has faced huge pressures, still battling higher energy costs, while facing possibly unfair competition from abroad. This week, the European Commission published a mammoth 700-page report on the effect of Chinese trade practices on Europe, essentially proving that China is dumping products because of politically-led rather than market-led production quotas. It highlights that Europe’s open markets have led it to feel quite extreme pain, especially in areas like electric vehicles.

Perhaps it also shows that the US tariff policy has protected its economy, but almost certainly concentrated the pain in Europe, highlighting the differing paces of political decision making (as if the need for a 700-page report didn’t do that as well).

Europe has little choice but to impose trade barriers like the US. However, this will be more difficult to enforce than in the US, given Europe exports more of its own goods (machines, cars, luxury goods) to China. One also wonders what this will do for China’s own policymaking. They have relied on external demand to support their economy while saying that they wished to expand domestic demand. However, President Xi’s philosophy is antithetical to individual consumption. There are anecdotes of many shops closing in the major city malls because spending appears so lacklustre. We write in a separate article about how the rise in gold prices may be linked to Chinese consumers and the path of the Chinese Renminbi currency.

We also touch on the travails of Thames Water and its holding companies. The holding company investors are already bearing a lot of pain but, currently, there are hopes among the holders of the main Thames Water bonds that they will be “kept whole” and that Special Administration can be avoided. If not, utility bond holders will be a lot less happy. Please drop us a line you would like to read them.