Inflation running out of money

Posted 28 April 2023

Over the past few weeks, we have observed how markets have been hanging in a fine balance, as evidenced by the rather directionless and decreasingly volatile bond, equity and currency markets. We are not the only ones who see it that way.

In particular, credit markets have been very stable or – as one could also interpret them – indecisive. There appears to be lots of investor demand for higher-yielding corporate bond securities without much new supply through issuance matching it. This demand overhang has cheapened credit spreads, or in layman’s terms the premium that corporates pay over governments.

However, for corporates, the interest cost is not just about the credit spread. Compared to 18 months ago, the absolute yield cost of debt capital, even for governments, has very rapidly risen to levels not seen for a long time. Against this, inverted government bond yield curves of lower yields for longer maturity bonds may be signalling that markets expect central banks to cut interest rates in the not-so-distant future. With the current total cost of capital at any maturity still higher than the return on capital that many companies appear to expect over the longer term, there is understandably little appetite among corporates to rollover existing debt, let alone create new finance. Instead, they appear to collectively try to sit out this yield high, hoping for better financing terms later in the year. We suspect many mortgage holders in the UK with their mortgage terms nearing expiry are having similar thoughts.

Back in the corporate world, for all those that need to raise equity finance, life is even more challenging.

For new equity issuance or Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), the US is now the world’s main venue. It used to be the UK, but that has changed in the past 20 years.

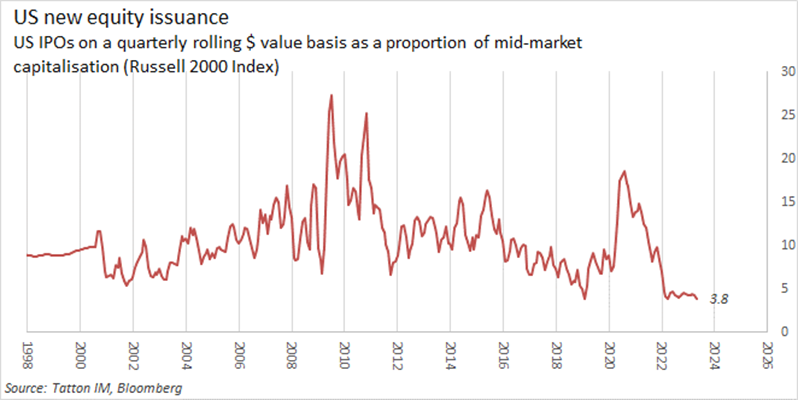

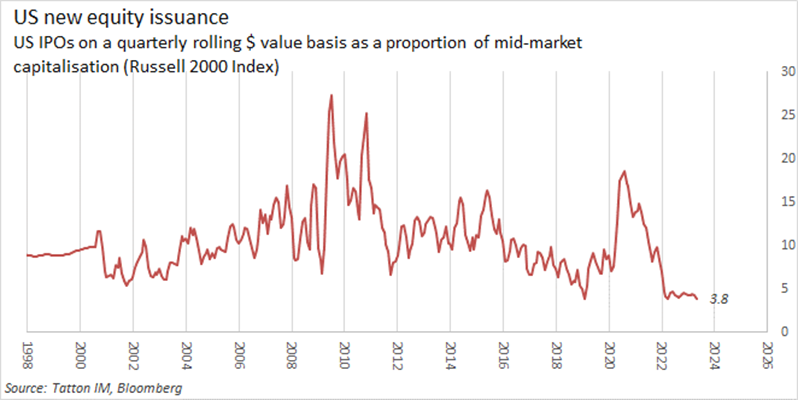

So, it is remarkable to see how quiet the demand to issue new equity capital has been. Below is a chart showing US IPOs as a proportion of the existing market capitalisation of the mid-cap Russell 2000 Index. We use Bloomberg’s monthly tallies, on a rolling three-month average basis. The

issuance level has been at very low levels since the start of the US Federal Reserve (Fed’s) monetary tightening and now is at 3.8% of the Russell 2000 overall market capitalisation. This is the lowest in the past 25 years, including the aftermath of the bursting of the dotcom era.

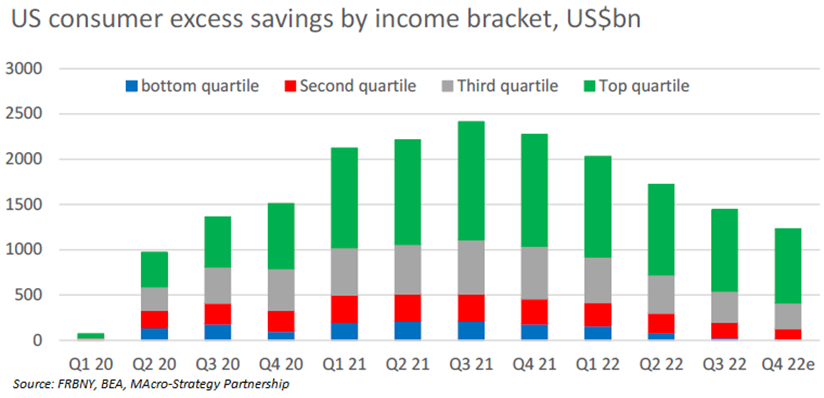

The pandemic period created a huge flood of liquidity which went out to individuals and companies. However, especially in the US, individuals were handed the money by the government, while companies had to borrow it. Some individuals went on to spend the windfall, others were savers. Perhaps inevitably, those who earned more before had less reason to spend the windfall. The chart below was initially developed by Fed analysts and has lately been updated by the MacroStrategy Partnership. It shows how the lower income quartile had probably spent most of

the windfall savings by the end of last year. On the observable trend, the second quartile are probably almost done by now. The upper half probably still have their windfall.

Knowing this (and the US is here merely serving as the representative of all western economies), central banks have set interest rates deliberately high to stem any additional new supply of money while the windfall money flooded back into the real economy in the form of consumer spending.

For us, it is reasonably clear that the remaining windfall cash is not going to be spent – it will remain as savings. It is ‘excess’ savings which have to buy up the available assets. We should be clear that this skews the usual messages about risks. Investors are not buying because the investment risks are lower than usual – no, they have too much liquidity and fear the impact of inflation on their surplus savings. Indeed, the behaviour of companies we described at the start tells us – and all informed investors – that, at current economic activity levels, they don’t think they can pay the going rate on capital. Their expected profit growth is low.

If activity is low and there’s little left in windfall money to spend, why is inflation still high? Should central banks still worry that an inflation spiral has set in?

This week’s earnings reports, here in the UK, Europe and in the US, provide more evidence of companies trying to offset weak (often negative) volume growth by raising prices. Unilever and Procter & Gamble were notable in this respect. Such behaviour has been termed “greedflation” and given historical precedent there may be some truth to this. However, as investors, we should recognise that we want companies to protect shareholder returns.

As indicated, such episodes are actually very typical as any economy slows down. Companies don’t like to use whatever pricing power they have, but they will if they have to. Inflation almost always goes up at the start of economic slowdowns. The problem for companies is that their micro-economically rational behaviour has in aggregate disadvantageous macroeconomic conse-quences – ‘the fallacy of composition’ – given such individual defensive action slows the economy further since the buyers do not have any more money to spend (Our cartoon this week refers to this, while reminding us these dynamics are nothing new).

We should hope that central banks recognise this as the last throes of a cycle, rather than worrying that the latest service sector-driven inflation data is indicative of a spiral. The windfalls are spent, activity is slowing, supply shortages are no longer an issue, and even the labour market has started to ease, while companies do not think they can return more than the rate of interest.

Short-term interest rates and long-term bond yields are clearly not in line with the private sector’s ability to generate returns at current moderate activity levels. If economic activity levels fall further, that gap will grow and companies will get more stressed. As we head into the next round of rate decisions, it will be important for companies – and the risk assets that represent them – that central banks tell us they recognise they have done enough and the growing need to turn. The Federal Reserve Open Markets Committee meets on Wednesday 3 May, the European Central Bank on 4 May, and the Bank of England meets on Thursday 11 May.

We saw a sharp pick up in bond financing activity at the start of the year when yields dropped down, and it may be that yields are actually not so far away from a more comfortable cost of capital level for companies. Moreover, investors are not fretting greatly, amid reasonable Q1 earnings reports. At least the larger companies are still generating growing, if not stellar, profits.

Market volatility picked up a bit this week but without market levels having changed a whole lot by the end of the week. Perhaps that’s no surprise given the importance of the next two week’s monetary policy decisions. The expectations are that we will get small rate rises but accompanied by the ‘cooing of doves’ – soothing sounds telling us that they expect inflation to cool and rates to be moved to less tight levels as inflation allows.

Therefore, contrary to the old stock market adage of ‘sell in May and go away’ it seems to us that ‘let May’s sway guide your way’ may prove far better guidance for investors this year. We will certainly be monitoring central bank messaging, and the market perception of it, very closely.