Mega techs under the cosh

Posted 6 August 2021

After an unexciting July in terms of investment returns, August has made a strong start, with US job markets figures delivering a much-appreciated positive surprise today, while corporate earnings reports continue to support elevated stock market levels across the Western world. The reporting period for the first quarter was very strong and this one has progressed in the same vein, although the pace of analyst upward revisions of earnings estimates has been tailing off in comparison to last quarter’s stellar upgrade path. Still, it has been nearly as good so far, with UK upgrades strongest this time (according to Factset’s aggregates). We look at the UK in detail in a separate article after an interesting Bank of England (BoE) Monetary Policy Committee meeting this week.

We have written at length recently about how rising bond yields can be a threat to stock market valuations, unless corporate earnings growth outpaces the yield growth headwind. Against that backdrop, the recent rise in earnings expectations confirmed by the latest quarterly earnings season has not generated as strong an equity market as might have been expected. In fact, while markets have risen somewhat, they have also become a little cheaper, as yields have fallen while earnings have risen strongly. This is good news for investors, as it provides a bit of a buffer should yields rise again – a prospect that is still very much with us. Only this week, Citi Research noted that it expects a rise in US ten-year (long) yields from 1.1% to 2.0% into 2022.

Given that central banks are edging towards a reduction of (yield supressing) monetary support on the back of expected sustained growth, this anticipation of gradually higher long yields seems quite justified. Provided earnings expectations continue to rise – as they should if growth does becomes sustained – that is a recipe for generally stable equity prices rather than big moves either way. We would be happy to see valuation levels ease back further as they did over the past months as this would provide for better-based, more sustainable valuations, even when yields gradually normalise upwards.

The week started with further indications that China is continuing its rapid pace of regulatory ‘reform’. Last week, online education companies were targeted. This week, it was about the negative impacts of computer games, and monopoly in music rights. China’s tech giant Tencent felt some pain, although it ended the week only about 5% lower than the start.

The compression of Chinese tech giants like AliBaba and Tencent has been met in the US and UK with some cognitive dissonance. Many investors are wary of the impact of mega-techs like Amazon, believing that their behaviour has destroyed general profitability. Yet investors also find it difficult to think that the Chinese authorities’ behaviour is about ensuring a level and fair playing field for its domestic businesses.

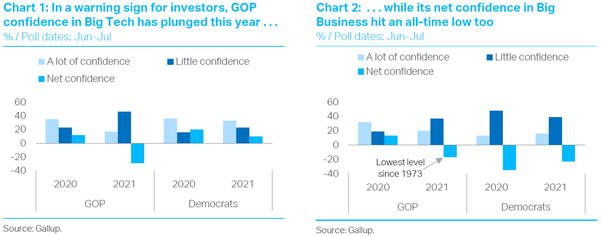

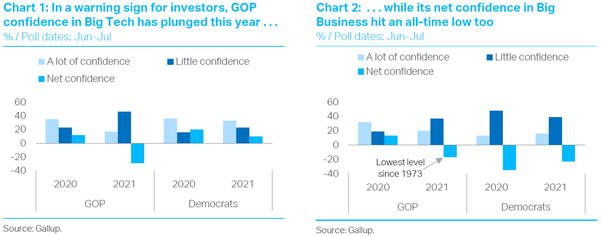

However, our research partners TS Lombard point out that similar efforts are gathering steam, especially in the US. Remarkably perhaps, the push may be coming from the Republicans even more than the Democrats. Grace Fan of TS Lombard comments; “Biden’s recent nomination of a Google foe, Jonathan Kanter, to head the Justice Department’s (DoJ) antitrust division confirms an inflection point in US antitrust regulation. For more than four decades, the consumer welfare standard has been the prevailing yardstick for US antitrust cases (the ‘Chicago School’). As a result, M&A deals were usually approved when there appeared to be no grounds of concern about consumer interests (i.e. there was no burden of proof about consumers actually benefitting, but a lower bar that they would not be seriously harmed). However, Kanter and other critics who belong to the ‘neo-Brandeis School’ have argued that this standard is both inadequate for the digital age and one that has led to highly concentrated industries, hurting workers and consumers alike.”

This follows the April appointment of 32-year-old Professor Lina Khan to chair the Federal Trade Commission, which shares anti-trust enforcement with the DoJ. As a law student at Yale, Khan came to prominence with a research paper on Amazon.com that cast the online retail giant as a harmful monopoly and argued for a rethink of antitrust enforcement.

Discussions about regulation are not the same as actual regulation. However, Biden has pushed various US agencies to act. His 9 July Executive Order called for 72 new measures across more than a dozen federal agencies to curb excessive corporate consolidation. For tech firms, this means greater scrutiny of both past and future acquisitions (including nascent rivals), as well as new rules to prevent excessive data collection, surveillance and ‘unfair competition’ in online marketplaces.

For tech businesses, the acquisitions have tended to be other US-based companies. For non-tech US businesses, it may mean looking outside the US for targets. Even then, the US blocked the AON/Willis Towers Watson merger despite it being a US/UK entity merger, because of the global nature of insurance brokerage.

Europe may not be so happy to see such approaches, although the UK government is likely to be a bit more welcoming. Lockheed Martin may not be able to buy Aerojet Rocketdyne but Parker-Hannifin can buy Meggitt.

While this means China’s regulatory approach may not end up being so different to the US or Europe, it does not mean China will automatically benefit from the apparent levelling of the playing field. Trump attacked Chinese companies like Huawei on security grounds and Biden is expanding, not reversing, this policy stance. This week, a ban on investment for a further 59 Chinese companies was put into effect. Indeed, across a whole range of measures, Biden is stepping up the pressure. TS Lombard expect Xi Jinping to be more reactive than proactive, but there will be a lot of potential reactions. After he is (probably) confirmed in his third term, just over a year from now, he may return to a more aggressive approach.

Returning to the mega-techs of the US, they face headwinds across the board. Their revenues and reach are big enough to mean that the secular excess growth of the past 20 years may already be difficult to sustain going forward. At the same time, the now-attained relative certainty of their profits in the future also mean that higher yields affect their valuations more than the cyclicals; tax policies will be targeted towards their profits; their acquisitive business models face significant pushback.

Rather than being just talk, policy change appears to be underway. Indeed, the new appointees to the various US agencies will be under pressure to act from both sides of the US political divide. The US mega-tech companies have enjoyed an incredibly supportive policy environment, and there is an increasing belief it will prove challenging to sustain shareholder expectations for future growth levels. We should not write them off just yet, but as always, a broadly diversified portfolio has a better chance of benefitting from growth opportunities, wherever they are.