New school term has the US back at the top of the class

Posted 1 September 2023

Summer is officially over, but we are none the wiser regarding the direction of the economy. Or are we? Well, we quite likely are, but just a bit and not enough to know if next month’s equity markets will be higher or lower than right now.

The broad market outturn was slightly negative with US stocks ending the month unchanged. India was the best performer by a very slight amount, but perhaps more importantly, it has shown a lot of price stability recently with the underlying economy doing well especially in export terms. This is somewhat different to other Emerging Market nations which have been more impacted by a slide in global goods trade. We write about India in the second article this week.

In the UK, house prices continue to decline as evidenced by the 5.3% year-on-year fall in the Nationwide August index reading. Prices fell 0.8% in August and the softening of the UK labour market suggests the falls could continue into the colder months as affordability further decreases. Although fuel prices have moved annoyingly higher in recent weeks, food prices appear to have stabilised somewhat with grain prices falling over 10% in sterling terms over the past year.

Generally, the UK’s inflation backdrop continues to ease, although not fast enough for comfort according to Bank of England (BoE) chief economist Huw Pill. He wants interest rates to remain high and steady (like the Table Mountain in Cape Town – where he made the speech); and suggests policy should be kept steady at restrictive levels rather than sharp hikes followed by rate cuts. Pill argues that the tight jobs market allows workers to push up wages which have previously been eroded by inflation, creating a dynamic that leads to inflation persistence.

Bloomberg reported that Pill said the BoE takes comfort from longer-term inflation expectations being much better anchored compared to previous surges in prices in the 1970s and 1980s. “That’s something we have to work on,” he said. “That anchoring of expectations doesn’t happen by accident. It happens because of the actions of the central bank and the commitment of the central bank to its inflation target.” Regardless, perhaps we should be happy he did not mention any immediate need to raise rates further.

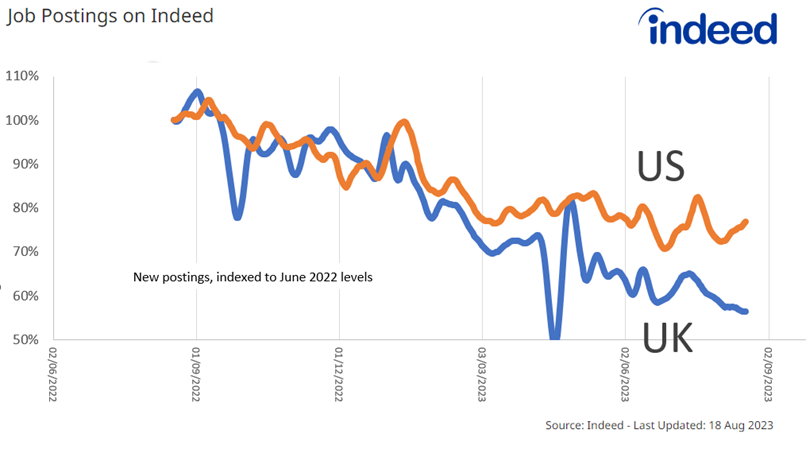

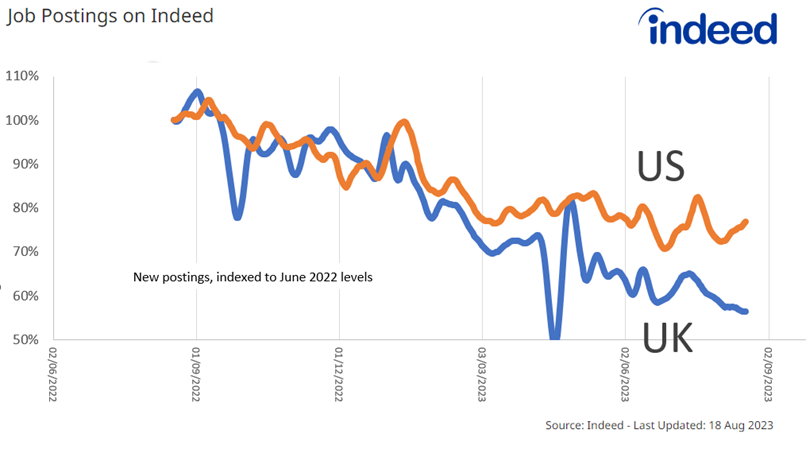

In terms of wage dynamics, one of the data sources for the employment market we observe most closely is the Hiring Lab team at Indeed. Their data shows how both the UK and US jobs market have eased but the slowing is more noticeable in the UK (see the chart below).

We conclude from this that – despite Huw Pill’s warnings – for the UK, the room for rates to come down is closer than he may want to make his audience believe. There are still ongoing wage disputes but these are fewer now that many of the NHS settlements have been done. Meanwhile, the UK government seems set on a mildly restrictive stance designed to help bring inflation down. For Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, this is a “must achieve”, so things may get even tighter.

However, the job postings data in the US market may be showing signs of picking up, despite the mild decline in the official August (non-farm payroll) employment numbers and the climb of unemployment to 3.8%. Bonds have been seeing yield declines through the week amid optimism that the US labour market is easing into non-inflationary territory, but the above chart suggests caution.

For us and for Steven Blitz, leading US economist at TS Lombard Research, the latest US GDP release contained an important signal – broad non-financial corporate profits rose in the second quarter, contrary to expectations. This is important because it appears the restraint on businesses and consumers imposed by higher interest rates has not been particularly impactful over the summer. Blitz argues that both companies and households spent the post Global Financial Crisis (GFC) years getting their balance sheets into good order, reducing debt and growing savings. That leaves the private sector in a good position, one which is not as much impaired by the cost of debt than has been the historic norm. Indeed, it seems that the private sector may be benefitting from the rise in interest rates, as interest income outstrips debt cost increases.

It’s the government and other public deficits which have worsened substantially. Of course, the pandemic would have always led to a sharp rise in debt levels but, for the US especially, the public sector balance sheet was already on a declining path following Trump’s expansive fiscal policy while cutting corporate taxes at the same time.

The extent of government deficits was a big topic at last weekend’s central bank get-together at Jackson Hole, Wyoming. We write about this in the first article below.

Large public deficits are not destabilising in themselves as long as confidence in the state institutions remains strong and the general financial environment is healthy enough to not deprive the private sector of the capital to grow. However, the current relatively large size of public debt relative to economic output across most developed economies give little room for emergency action if needed. We certainly would find another pandemic problematic.

More importantly and likely, the deficits have to be stable on an ongoing basis rather than expanding because of interest costs. In the US, revenues are just about adequate but projections of stability require an assumption that many of the Biden programmes have an endpoint. Such time-constrained spending programmes tend to get extended. Thinking that the US will move into recession because the government will constrain expenditure flies in the face of history, especially around election years. Europe’s position may differ slightly in detail but not broadly in direction.

However, there is a significant difference when we compare economic growth as all the above suggests that the US economy is not being obviously held back by the current higher rates. Whereas house prices are falling in the UK, the US-wide Shiller index of house prices showed another rise in the latest month (June data). The index has been rising since February and is now back to its previous high seen in June 2022. The nature of the US housing market is that housing purchases are mostly in new homes, which in turn is having a positive impact on growth.

Following significantly tighter financial conditions over the second quarter they have recently eased back as corporate lending premiums (credit spreads) declined on spreading expectations that the US economy will avoid recession. Profit expectations have started to rise as well on a next 12-month basis, partly because analysts are not bringing down their expectations for 2024 as they usually do as the year ahead draws closer. This may change, but recent guidance by companies is not compelling them to do so currently. While the stock market is giving high valuations to those profits, should profit growth prove to be achievable, equities would remain underpinned despite continuing high rates.

Such economic resilience despite all monetary tightening of the past year-and-a-half would not be comfortable for the US Federal Reserve (Fed). While Huw Pill may worry about the UK’s inflation persistence, the US economy would be far more likely to have a problem with sticky inflation as the labour market would remain tight. US bond yields may have fallen back recently on slight economic sogginess but we think it unlikely they will go too much further. Given the lag in economic dynamics in Europe and the UK, they have got more room to ease here.

So, are we any wiser at the end of months of seemingly economic procrastination, plateauing of interest rates, disappointing China news and fearing about imminent recession? Well, the general economic development has by and large withstood the monetary onslaught much better than expected while inflation has come down progressively. This tells us that despite widespread fears that after ten years of ultra-low interest rates, the return of ‘old normal’ levels of interest rates would spell imminent economic and market disaster are probably premature.

As a result, markets have been much like the past summer months in the UK – not so hot but not disastrously cooler. Companies and households have been prepared for difficulties but it hasn’t been so difficult. Let’s hope the autumn is full of warmth, mists and mellow fruitfulness.