Recession fears creeping back

Posted 6 October 2023

The balmy autumn temperatures have continued into October, but the market chill that has also carried through from September is more troubling. We discuss the asset class returns of the past month and quarter in our next article.

Financial markets are in one of those occasional periods where the world’s economic realities do not quite seem to match what some asset price moves seem to want to tell us. This week, and continuing the trend from last week, we saw a further rise in global long bond yields despite some weakness signals from the global economy. The 10-year US Treasury benchmark hit a yield of 4.88% in early trading on Tuesday – the highest point in 15 years. Other government bond markets duly responded, although rose slightly less. Because of the inverse correlation between yields and bond valuations, this means that fixed-interest government bond prices fell. Subsequently, yields fell back from the highest levels but are now heading back towards their highs after another extremely strong US jobs report. Across the board, they are 0.15%-0.30% higher than last Friday which equates to a fall in in the global bond index price of about 1.5%.

At the time of writing, global equity markets have broadly slipped by about 2.5% in GBP-sterling terms, mostly (we calculate) due to the valuation impact of rising bond yields rather than pessimism over economic growth and any impact on earnings.

However, commodities have also come under pressure which does seem to be related to traders’ fears that growth will be lower than previously anticipated. In particular, oil prices have reversed all of the rise seen in September. Brent spot crude fell 13.5% in just three trading days and is back to $85 per barrel, the same as on 29 August. Industrial metals, which actually fell in September, continued to decline about 4%. Commodity investors seem to be more downbeat about global growth than others.

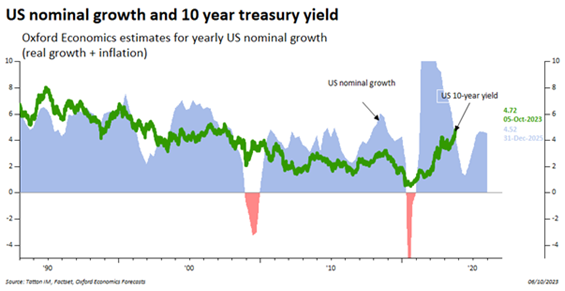

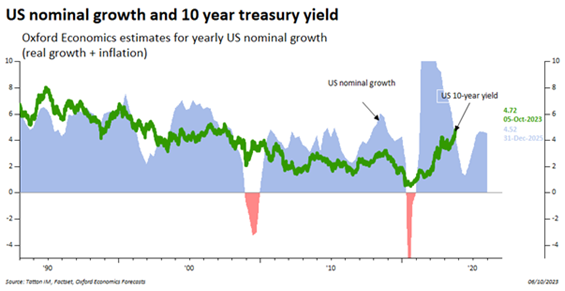

Regular readers may at this point think, hang on …. hasn’t Tatton written in the past that bonds are supposed to be the best barometer of economic health? Don’t yields rise when economies are doing well and fall when the economies are having a tough time? And they would be right. For much of the time, bond yields reflect the broad level of economic activity, both real growth and inflation (we refer to this aggregate as nominal growth). Below, we show a chart of the US 10-year Treasury yield (in green) and US nominal growth since 1990 with data and estimates from Oxford Economics:

Like most forecasters (and ourselves), Oxford Economics foresaw a US slowdown coming during 2023 and has been surprised (as we have) by its resilience. Indeed, there is no denying that the forecasts for a slowdown this year have proved wrong – in the US and even here in the UK. Global intermediate and finished goods trade has clearly slowed but demand for services has been solid. Economies that are more services-heavy have done better than expected (such as the US, UK and to some extent, Japan), those that are goods-based have done poorly (China, Germany, etc.). Services employ more people so the jobs market remains supportive, people remain reasonably confident and prepared to spend.

Nevertheless, a slowdown is still likely as the pace of fiscal stimulus wanes through next year. And the rise in yields makes a slowdown more likely, not less. For many people and for large businesses, their cost of new borrowing is more related to long-term rates than short (for example, US mortgages are 30-year fixed), so the squeeze is getting worse.

So why have bond yields gone up? We think that some (perhaps quite large) investors became overconfident about an ‘imminent’ slowdown earlier this year based on the economic sentiment indicators like the Purchasing Manager Indices (PMIs)a. Rarely do these indicators give false signals but this appears to be one of those times.

Some investors locked in what appeared to be attractive yields. For them, the latest yield increases constitute a missed opportunity but not much else. For investors that borrowed money to bet on falling yields on longer maturity bonds (as hedge funds can do), the price movements have been very painful and for an extended time. These are the most likely to capitulate now. The unwinding of their positions creates a price dynamic which says little about changed market expectations and much about past errors of judgment.

Other investors bought longer maturity bonds and sold equities, expecting a slowing economy leading to general falls in earnings expectations that would hurt stock markets. As it happened, the valuation impact from rising bond yields has hurt stock prices but not the earnings expectations side, as in general, equity analysts have held their 2024 forecasts for larger cap stocks steady. So the damage has been limited so far, generating only a lacklustre quarter for asset returns on the back of just the yield-driven valuations component. The Q3 earnings announcement season begins slowly next week, but will build to a crescendo as we head into November, just as all the central banks make their next rate decisions. Earnings are likely to bear little in terms of negative surprises, but business leaders’ forward guidance may force down analysts’ 2024 earnings expectations.

Market volatility has shifted up across all asset classes which suggests global market liquidity is getting tighter – not surprising, given the continued drain by central banks and the substantial losses across bond markets and, to some extent, commodity markets. Tighter financial conditions make it more likely that growth will slow so we suspect that, in themselves and just like with oil, higher bond yields now probably mean lower bond yields later. For equity and credit markets, it may be that bond yields plateau and then fall without too much impact. However, the tightening of liquidity is not a helpful signal and the risks of a sharper bout of volatility are clear. Bond yields will probably come down more so if risk assets are under pressure but that may this time be because economic weakness undermines earnings projections and equities would then find it difficult to rally substantially just on declining yields.

For equity and credit markets, it may be that bond yields plateau and then fall without too much impact. However, the tightening of liquidity is not a helpful signal and the risks of a sharper bout of volatility are clear. Bond yields will probably come down more so if risk assets are under pressure but that may this time be because economic weakness undermines earnings projections and equities would then find it difficult to rally substantially just on declining yields.

Ahead of the next round of rate meetings, central bankers could make things worse if their comments were seen as hawkish. However, inflation data are likely to be helpful rather than a hindrance so we should perhaps expect them to sound slightly dovish in the next few days and weeks. We certainly hope so.