US election market impact – not straight forward

Posted 2 October 2020

Selling pressure built up early in the month, as COVID cases spiked around the world once more. The fear was that we were in for a repeat of March, where the spread of the virus and ensuing global economic shutdown sent markets into a panicked frenzy. But this time, level heads prevailed. While asset prices traded either sideways or down throughout the month – depending on the region and currency basis -no ‘sell everything’ fever took hold.

In sterling terms, the best regional performer – by some distance – was Japan. Japan’s Nikkei 225 climbed 4.6% in September, with the MSCI Emerging Market index the next-best performer at 1.9%. US equities, having done so well in the recovery rally from April, fell 0.4%. Most interestingly, Technology (the market darling of the last few years) was the worst-performing US sector. The tech-heavy Nasdaq index fell 1.7%, as investor optimism for the all-conquering mega-caps began to wane. Still, even after letting off a bit of steam, US tech remains up 28.4% year-to-date.

Looking deeper into the tech world, The big five – Microsoft, Facebook, Amazon, Apple and Alphabet (Google) – are up an average of 39.7% year-to-date, while the median US stock has fallen 6%. Those five companies now account for a record 23% of the entire value of the S&P 500.

UK stocks, meanwhile, continue to lag behind their global peers. The FTSE 100 once again had a rough month, down 1.5% in September and now negative 20.2% year-to-date. The double whammy of a significant economic and public health crisis – worse than any other G7 country – and damaging Brexit risks is hampering businesses. How and when these two factors will stop weighing on Britain is difficult to say, but investors should at least be consoled that, as globally diversified investment portfolios, UK assets do not constitute the predominant part of their overall investments. It is global growth – and global asset markets – that are far more important.

Overall, September’s price moves look more like the consolidation of a strong run than the flight of frightened investors. Nevertheless, market jitters were far more prominent than over the summer, with far larger price swings. As we wrote recently, commodities have been at the head of this bout of volatility – with Bloomberg’s commodity index losing nearly all its August gains last month. A substantial part of this fall was driven by oil prices, which fell 3.2% in September and are now 31.9% lower year-to-date. Gold, on the other hand, is still the second-best performing asset among those we track, up 27.5% in 2020.

Volatility goes hand in hand with the ‘wait and see’ narrative coming through in capital markets. The hopes of a swift V-shaped economic recovery that drove markets over the summer have been dashed by second wave fears, diminishing fiscal support from governments and a generally slowing rebound. The jury is still out on how long lockdown restrictions will need to last, and how quickly a vaccine – which would save lives rather than restrict social activities – can be produced and rolled out at scale.

If a vaccine which protects those most at risk can be achieved before the end of the year – or if the public health risks from the ‘second wave’ are not as great as what we saw during the first bout of COVID (which the experiences of Spain and France suggest) – we should expect the economic recovery to resume. Even in that case, activity is unlikely to rebound as quick as we might hope – with reluctance of the more fearful to return to their former lifestyles not necessarily outweighed by gushing spending and activity increases by the demob happy young and fearless.

That realistic outlook makes the second prong of the recovery – policy – all the more important. With consumers and businesses struggling to survive, central bank and government support has been vital. Central bankers have seemingly now committed to doing their part: keeping rates low and liquidity flowing for the long haul. But the fiscal side has recently left a little to be desired. Support is being handed out with less zeal than earlier in the crisis, and in some cases not handed out at all, which could drastically slow the recovery.

Unfortunately, the longer restrictions must remain in place, the more opportunity there is for a policy error. The biggest danger of this is in the US – where bitter political divisions seem to be hampering the progress of getting fiscal support to those who need it. We can take some comfort in the fact that both presidential candidates are likely to give some level of fiscal stimulus, but it is needed sooner rather than later. Thankfully, we can bank on Donald Trump going to any length to secure his re-election, and if that means further spending measures in the next few weeks, that is what we should expect. If none are forthcoming, there is a real danger that this forced recession could turn into a ‘classic’ downturn – driven by widespread corporate defaults and rising unemployment.

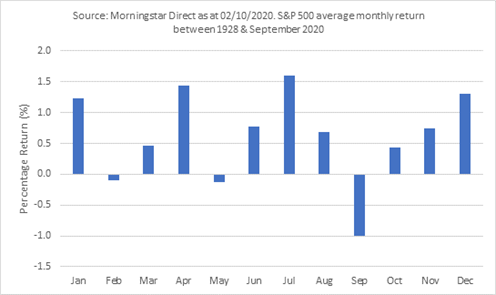

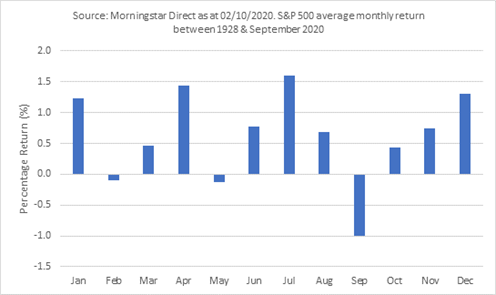

Finally, we end with a note on historical monthly returns. While last month’s market returns were a little disappointing, they were normal by historical standards. Interestingly, September is on average one of the worst months for market returns, dating all the way back to 1928. Perhaps investors prefer to take their profits after having taken stock of their investment over the course of their summer holidays.

By any standard, this week’s US Presidential debate was ugly. With just over a month until Americans head to the polls, the Trump/Biden clash was packed with pithy insults, but exceedingly light on policy. President Trump characteristically tried to steamroll his challenger, constantly interrupting Biden by attacking his political record and his personal faculties. The Democratic nominee, on his part, managed to avoid any of the big gaffes that have plagued his campaign, and even managed to deliver the night’s most memorable soundbite: “Will you shut up, man!?”

Judging from the betting markets, it was Biden who walked away from the fight in better shape. Betfair Exchange puts the odds of a Biden victory at around 60%, up a meaningful 5%. Indeed, the polls on candidates’ policies and performance also point to higher marks for Biden. But talk of him ‘winning’ this debate may be a little hasty. Nobody really won here, and it is unlikely that the showdown did much to change anyone’s mind decisively.

That in itself is a positive for the former vice president, however. Biden did not have to win the battle of bluster; he just had to not lose. Trump trails his opponent 6-8% in national opinion polls, and by a slightly smaller (though still tangible) margin in the all-important swing states. Despite the polls, Trump’s sizable re-election probability was likely in part down to the expectation of a late surge – spurred by Biden taking a bruising in debates. That did not happen, and Trump’s bulldozer performance seems to have done little to gain him support – even if it did not lose him any. Friday morning’s news that Trump has contracted COVID-19 and gone into self-isolation is unlikely to turn things around for him, given he has always portrayed the danger of the virus as exaggerated and often refused to wear a mask. Given this now also robs him of about one-third of the remaining campaign time, the only way this could slightly play into his hands is if his course of infection turns out to be very mild.

Barring any more October surprises, a Biden victory has become a reasonable base case. At first glance, that seems like a negative for capital markets. Trump has made deregulation and tax cuts a central part of his economic policy, while Biden’s plans involve an estimated 12% hike in the effective corporate tax rate – roughly back to where it was under President Obama.

Even if Biden was to win of course, implementing his proposals unchanged would be extremely unlikely, as the Republican Party is still favourite to retain control of the Senate. But over the last four years, Trump has shown the immense policy power of the executive order – something we expect to become a permanent feature whatever the election result, given the partisan logjam in Washington. And yet, US equities have been stable over the week, even rallying somewhat on Wednesday following the debate. Why are equity markets so sanguine about this probable tax rise?

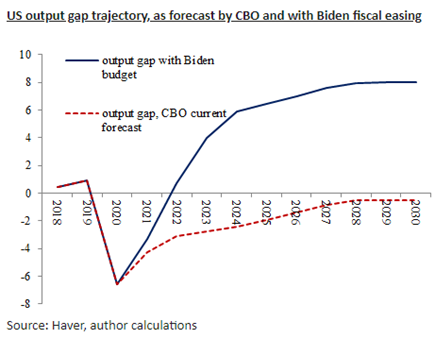

Obviously, there is far more to equity values than a country’s tax regime. A potentially larger effect from Biden’s plans could come from the sizeable fiscal boost on offer. Biden plans to spend significantly more than his opponent in aiding the US economic recovery. Compared with the current plan from the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), Biden is expected to add a 1% fiscal boost next year, followed by two years with a 3% boost, and another year at 1.5%. The calculations involve only ‘first round’ effects but, nonetheless, give an idea of the extent of stimulus. Tim Bond of Odey Asset Management has produced the chart below, which shows the difference in output gap between the CBO’s current forecast and Biden’s plans. The stark difference would lead to a significant growth spurt for the US economy.

Whether that is a positive for equities is a little more complicated. Throughout the pandemic – and long before – one of the main market underpinnings has been the unprecedented support provided by central banks. By keeping interest rates pegged at zero and injecting vast amounts of capital into the financial system, monetary policy has drastically lowered the ‘risk-free’ return of real (inflation-adjusted) government bond yields. With returns vanishing in the bond market, investors have nowhere to go but equities.

The US Federal Reserve (Fed) has recently committed to a ‘lower for longer’ policy on interest rates, going as far as saying it is willing to let inflation run above its 2% target for some time to aid the economic recovery. But if Biden can boost medium-term growth with his fiscal plans, it could create upward pressure on inflation. If so, the Fed could rethink its tolerance for overshooting inflation – tapering back its bond purchases and possibly even raising interest rates sooner than expected. If this led to a sharp spike in bond yields, it would likely cause a re-rating of equity prices, pushing down risk premia (the amount investors are willing to pay for a given level of risk). Equities would become less attractive compared to fixed income investments – put simply, the government bond yield would have become more attractive again compared to the equity yield. This could put downward valuation pressures on equities if investors felt that the economic growth only led to higher government yields, but not also improved earnings on the corporate side.

Tim Bond sees the case for this. If long-term 30-year rates were to move towards 3.5% from the current 1.48%, and the corporate tax rate were to rise to from the current estimate of an effective 14% to 26%, his view is that it might mean as much as 30% downside for the S&P 500.

We are much more sanguine. In our view, economic growth would drive up corporate profits, and would likely more than offset the effects that tax hikes might have on equities over the medium-term. Even assuming a bullish scenario for growth and inflation, it could take many months before markets question the Fed’s grip. We would expect fixed income bond markets to remain orderly, and therefore a re-rating of equity valuations should not outweigh the benefits of improved profit growth. Indeed, it might mean that real yields move further down, the scenario which has historically been very supportive for risk assets.

JPMorgan is similarly positive on the outlook for US equities and credit markets. It expects the S&P 500 to reach record highs of 3,600 by the end of 2020, with improved corporate earnings this year and next. On this view, a Biden victory is neutral or even slightly positive, rather than the negative equity scenario some are painting.

That said, should US corporate taxes increase while inflation runs hot, US bonds and large cap equities would become relatively less attractive compared to their global peers – pushing down the value of the dollar. That situation – a booming US economy with a weak dollar – has historically been a major boon to the world, even if US equities themselves do not reap a benefit relative to other regions. Emerging market assets would do well out of this, particularly if a Trump loss led to a less impulsive US trade policy.

In particular, the US tech superstars – the big winners of recent years – could face tougher times than most. This is arguably something that needs to happen regardless, and could be seen as a sign of a healthy sectoral rotation. If the Democrats do indeed sweep the election (winning the Presidency, House and Senate) we see better investment opportunities in sectors like materials and industrials – the classical cyclical winners.

The worst-case scenario for equities would be if Trump lost the election but refused to accept the result – no doubt resulting in widespread civil unrest. It is unlikely that he would be successful in challenging the election result, but it is a risk nonetheless. For now, it looks like a Biden victory would, overall, not be negative for US equity markets and indeed may be good news for markets across the rest of the world.