Markets catching up with reality

Posted 23 June 2023

Following three weeks of ‘not a lot of news’ being good news for stock markets, bad news dented investor sentiment this week. This has coincided with some reversal of global liquidity as the US government is once again stepping up fundraising to replenish its coffers and Pan-European business sentiment surveys ticked down. No surprise then, that risk assets experienced a mild sell-off that reversed some of June’s gains. Hardest hit were China, Europe and the UK, but for inherently different reasons.

China suffered from a paucity of information. After having created much anticipation of policy action in early June, its central bank edged rates lower while the government failed to announce any concrete support measures. China’s equity market therefore unwound some of its recent outperformance. We write about the recent disappointment in the second article.

It was a ‘big’ week for the UK in information and sentiment terms. We write below about the UK’s interest rate rise, inflation data and bond markets. There is no doubt the UK’s data even had an impact on economist and investor views across other regions, but the UK’s stubbornly high inflation now clearly stands out against its peers’ falling rates of inflation.

Looking back over the past year-and-a-half, Europe, the UK and (to a slightly lesser extent) the US have faced very similar input cost pressure from rising energy, food, and commodity prices. Now the energy, food and commodity price pressures have eased, which has led some economists to predict a path of ‘immaculate disinflation’ – namely falling headline inflation, leading to falling inflation expectations, lower wage settlements, continued sustained profitability and growth – and the avoidance of recession.

But some economic research groups, such as Fathom Consulting, have been warning for months that the second and third-round effects of inflation caused by the initial shock of goods and energy prices were feeding through and should not be underestimated. This week’s data strengthens their case – particularly for the UK. Until recently, the west’s experience of inflation was broadly similar. So too were the structural issues, with tight labour markets pitted against companies with strongholds on their markets and savings-rich consumers making up for spending less during the pandemic years. Therefore, why would the UK be different from other regions?

We have noted before how surveys of inflation expectations are helpful only to historians. What matters is inflationary behaviour. Some of this behaviour can be observed in wage negotiations (and the degree of conflict the parties are willing to withstand, usually seen as strikes), and actual price setting. Another is in the levels of borrowing. If a company can be confident that current levels of revenue and profit growth have stepped up despite inflation and rises in interest rates, they will borrow to grow their business.

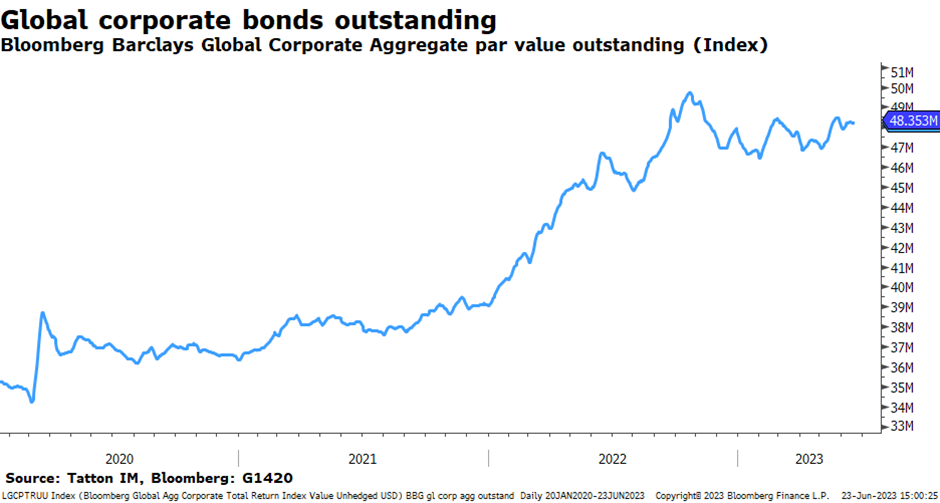

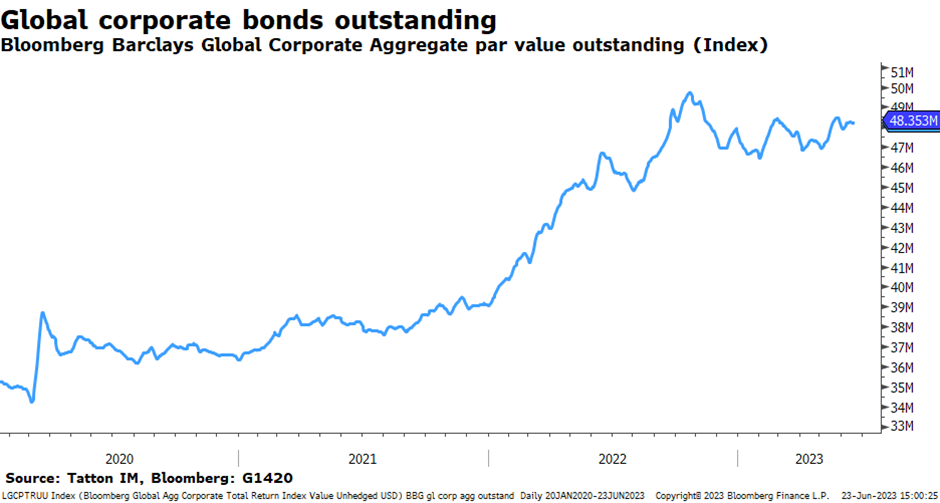

The outstanding amount of corporate bonds (as calculated by us from data from the Bloomberg Barclays Global Corporate Aggregate Index) is shown from the start of 2020.

After a huge take of borrowing in the early part of 2022 amid the start of rate rises, we got to a high point in October. This was when global activity started to show responses to the rising rate pressure. Subsequently, companies pulled back, only to go on a spurt of borrowing at the start of 2023 and then again during May as bond yields and credit spreads temporarily fell back.

That coincides with the burst of liquidity in markets seen during the following weeks. Now, we know we shouldn’t read too much into such indicators. Other signs from the loan markets and from the wider monetary measures tell us that things have been tighter, especially for smaller firms that have to raise debt through banks. However, we also shouldn’t ignore them. The willingness to borrow suggests that, at least for the larger companies, they are willing to rollover their borrowing at the higher rates rather than try and reduce their debt piles significantly.

This poses a conundrum for the central banks, of course. They were very hopeful that input cost falls would lead to ‘immaculate disinflation’, but the UK experience says it might not happen for them. While the UK’s situation is exacerbated by its own particular issues, there are enough issues in common for the UK data to be salutary for everybody.

That means central banks’ stated bias towards more tightening should be seen as meaning at least one more round of rate rises. Liquidity, which moved up in the second quarter, is likely to be squeezed again through the summer. Against that backdrop, risk markets are unlikely to storm away.

However, despite the many discussions about loss of central bank credibility, long-term real yields (i.e. after subtracting inflation expectations) are stable at around 1%, with long-term market expectations of inflation between 2-2.5% (except for Japan). Meanwhile, credit spreads are at mid-to-lowish levels, thereby indicating few concerns of capital markets about a looming recession. These are indicators of stability and, in central bank terms, success.

We only have to look at Türkiye to see what central bank (and government) failure actually looks like. Following his election victory, Erdogan appointed a new economy tsar, Mehmet Simsek, who has persuaded the president that orthodoxy must be restored. Hopes were that this would mean getting rates up to near inflation levels (currently +40% year-on-year). Rates were raised from 8.5% to 15% on Thursday, and the Türkish Lira slumped another 7% after the 20% decline following the election.

Sterling is not showing such a decline. In fact during the last three months’ inflation surge, sterling has strengthened.

If the resolution to the inflation problem lies in overcoming a structural shortness of labour – and in the UK’s case free trade – then central banks cannot solve it with what’s in their toolkit. Structural, supply-side problems can only be dealt with by far-sighted government policies in conjunction with a discouragement of inflationary demand-side behaviour. Of course, the former takes time and money, and it doesn’t feel like we have a lot of either of those at the moment. Nevertheless, we hopefully have serious politicians with the staying power to see it through.

The resilience of sterling and the positive real yields tell us markets are currently giving politicians (and central banks) the benefit of the doubt. However, this does not yet equate to a stable market environment based on the expectation of a return of sustained growth. Such fragile sentiment is therefore easily disturbed by wrong-footed political action or unanticipated data points, as was the case over the past week.